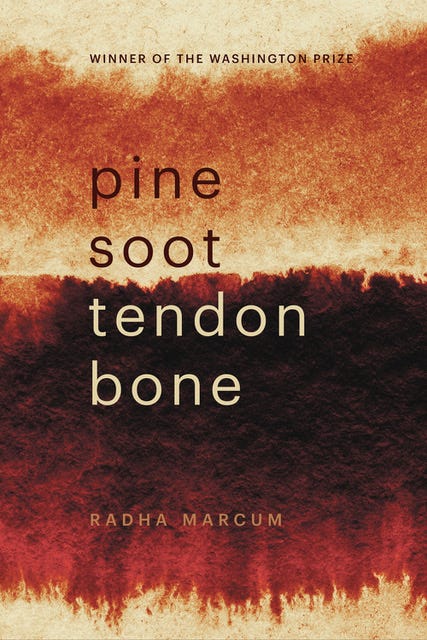

This week I was delighted to return to Lyons, Colorado, to talk about ekphrasis and how that practice inspired poems in my new book. The book title Pine Soot Tendon Bone comes from “Hidden Narrative,” an ekphrastic poem inspired by this painting.

I’m fascinated by the invisible traces—hidden narratives—in landscapes. In fact, the library where gave the talk overlooked the St. Vrain River. My husband and I lived literally just across it a couple decades ago. During the 2013 flood, the home we once rented (we were living in Boulder by then) was completely destroyed. The lot was divided and sold to adjacent neighbors. Nothing remains. But I feel those traces looking at the river.

Reading the hidden narratives in landscapes is similar to reading artworks in ekphrasis—letting an artwork permeate the mindscape until it turns into language. It’s similar to the practice of opening to sense impressions in a landscape, except that we’re experiencing traces of an artist’s mind in the canvas, sculpture, etc.

What is Ekphrasis?

Ekphrasis is describing or responding to a work of art—typically visual art, such as a painting, sculpture, or photograph. The goal of ekphrasis is not just to describe the artwork but to convey a personal reaction to it, exploring the subtle meanings, emotions, or connections that the art evokes.

Historically, ekphrasis can be traced back to ancient Greece, where it referred to detailed descriptions of visual objects, but over time, it has come to focus more on the interaction between the artwork and the writer's imagination. The classic example of ekphrasis is John Keats' poem "Ode on a Grecian Urn," where he meditates on the scenes depicted on an ancient vase.

What Ekphrasis Reveals

Many contemporary poets engage in ekphrastic writing, and this practice offers valuable insights into the process of writing poems in general.

Ekphrasis is a clear example of how poets begin with nonverbal sensory details and gradually move toward language. It emphasizes noticing, meditating on, and connecting vivid details to create poems that are not merely descriptive but experiential and evocative.

The process begins with concentrated attention, focusing on a single sensory field—vision for a painting or sound for music. But the mind doesn't stay there. One sense stimulates another. A distinct shape in a painting may resonate with a memory or dream. Colors and tones evoke emotions. In moments, language emerges and begins to interact with nonverbal sensations, memories, ideas, and images. We enter into dialogue with the artist's mind. The same thing can happen when contemplating a landscape or other natural phenomena. The vivid expression of the artist or ecosystem merges with our own, and the distance between ourselves and the world dissolves. It’s alchemical.

An ekphrastic poem—like any poem—acts as a spell, an incantation through which others can experience the vitality that comes from contact with art, nature, and our creative impulses and insights.

Parallels in Processes: Painters & Poets

I’m also particularly interested in how poets and visual artists share approaches to process—translating and synthesizing details beyond mere representation. Take these, for example …

Georgia O’Keeffe:

“I had to create an equivalent for what I felt about what I was looking at – not copy it.”

“I said to myself, ‘I have things in my head that are not like what anyone has taught me—shapes and ideas near to me—so natural to my way of being and thinking that it hasn’t occurred to me to put them down.’ I decided to start anew to strip away what I had been taught."

“Nothing is less real than realism. Details are confusing. It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis, that we get at the real meaning of things.”

“I often painted fragments of things because it seemed to make my statement as well as or better than the whole could.”

Agnes Martin:

“Art is the concrete representation of our most subtle feelings.”

“To be an artist, you look, you perceive, you recognize what is going through your mind. And it is not ideas. Everything you feel and everything you see and everything that your whole life goes through your mind, you know. But you have to recognize it and go with it and really feel it.”

“If an artist looks outward in life, we say that his work is visual, and that’s not a compliment. And if his work is intellectual, we say that it’s brilliant, and that’s not a compliment. And if it is made with the inner eye and the emotions that go with it, we all agree that that is the work with the most value.”

“My paintings are not about what is seen. They are about what is known forever in the mind.”

“When I first made a grid, I happened to be thinking of the innocence of trees, and then a grid came into my mind and I thought it represented innocence, and I still do, and so I painted it and then I was satisfied. I thought, 'This is my vision.’"

Kimiko Hahn:

“Why shouldn’t white and gray be an opposite pair; or take one color and allow an infinite splitting off. Such opposites, such contradictions, create energy in a poem.”

“My father, a visual artist, told me that it was easier to paint evil things than good—hence I grew up with large canvases of medusa, skeletons, bird-with-teeth.”

“All my material issues from deep and very personal concerns whether it’s for girls to be able to express anger or the melting of glaciers.”

Arthur Sze:

"My mother was a painter, and a frustrated painter. She started figuratively and then she went into abstract expressionism, with large blotches of color. I think she was never quite satisfied with her painting. So I had that personal contact growing up, of watching someone in the family painting and working with brushes and canvas. I have a keen interest in calligraphy, which combines language and painting, where they get wedded in that kind of way. The juxtaposition of images can be like these flashes of paint.”

“My poems can be difficult. … But line for line, my lines tend to be very clear. I value that precision of language, that clarity of perception.”

“I think one of the issues has to do with the tension between succession and simultaneity. Traditional narrative poems tend to be in that mode of succession, like Wordsworth. But our world is so much more complex and simultaneous now. I think, or I want to propose, for me one of the sources of this tension comes out of linguistics, or out of the way Chinese characters are created and juxtaposed. So if, for example, you want to write a word for “autumn” you write the character for “plant-tips” or “tree-tips” and then you juxtapose with the character for “fire.” So the character for “autumn” is then “tree-tips on fire.” Or if you want to write “sorrow” you put the character for “autumn” above the character for “heart or mind,” which I find fascinating. That simultaneous energy is there. If you look at “sorrow” you have “heart and mind,” and you have “autumn,” and you have “plant tips on fire” all happening at once. One isn’t prioritized over the other, which I think is part of the beauty and strength of it.”

“I think … instead of thinking that the infinite is somewhere far away, that it's actually right here. And one of the things that poetry can make us see and experience is that things we think are really far away, all the possibilities are really right here in front of us.”

How does visual art inspire or inform your poetry?

Share in the comments.

Upcoming Events & Workshops

How to Publish Poetry — Lunch & Learn (Virtual)

Are you working on a full-length poetry manuscript or chapbook, or building a portfolio of journal publications? Learn how to work smarter and overcome common obstacles to getting published during these monthly sessions in 2024. Jump in any time. Our next session is November 6th. Get a free guest pass.

Pine Soot Tendon Bone

"Radha Marcum writes unflinchingly and with a rare synthesis of lyric and scientific intelligence, investigating just what it is to exist with consciousness now.” —Carol Moldaw, author of Beauty Refracted

Radha, I'm so happy you posted this. I have leaned heavily into ekphrasis in 2024, participating in most of The Ekphrastic Review's biweekly challenges and other events. I have two collections in progress but am unsure about where to send individual poems and the manuscripts for publication. I've also been pursuing Smithsonian Associates' World Art History Certificate as well as Mary Hall Surface's Writing into Art workshops. Just the exposure to so many forms of art is so wonderful. As soon as I'm cleared from an autoimmune medical lockdown, I want to get to a couple of art museums in the Northeast. Go into the lesser-traveled galleries, study the work, record my impressions.

This has me thinking, maybe we can, and do, practice ekphrasis on anything: an orange on a table, an orange on a tree, an orange in your hand, and orange rolling down the street. Maybe we need something to follow until we find what we weren't looking for. What do you think?