Deep Play: The Long Game of Poetry

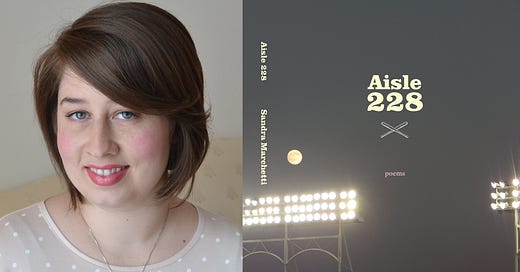

An interview with Sandra Marchetti, author of Aisle 228, a new collection of poems about baseball

April is national poetry month—and the start of baseball season. What better way to celebrate both than with this interview with Sandra Marchetti, author of Aisle 228, a new collection of poems about the Chicago Cubs and baseball.

We discussed:

Writing and revising poems as deep play

Why baseball makes for compelling poetry

How the book started—then took years to cultivate

Tactics and perseverance in looking for a publisher

Sandra Marchetti's baseball writing, poetry and prose, appears widely in FanGraphs, Baseball Prospectus, Blackbird, Fansided, The Southwest Review, and elsewhere. She earned an MFA in Creative Writing from George Mason University and now serves as the Coordinator of Tutoring Services at the College of DuPage in the Chicagoland area. She is also the author of Confluence, a full-length collection of poems from Sundress Publications (2015) and four chapbooks.

Watch the video below, or keep scrolling to read the interview. To hear Sandra read poems from Aisle 228, check out the video (I highly recommend it).

Deep Play: The Long Game of Poetry

Radha: I would love to start with a question I get from students a lot, which is: Should I try to publish a chapbook or build a full-length book? You've done both. How do you think about these two choices in publishing?

Sandra: What I've learned is that some projects really lend themselves to being chapbooks, but even a book project may may lend itself to having a portion that can be separated out as a chapbook. Others don't. Before this book that I just published, Aisle 228, I put together a chapbook manuscript on a whim and sent it to one contest. And it just didn't feel right as a chapbook. I felt like it was a longer story. It needed space to be told. You know how literary magazines suggest you can send a novel excerpt that makes sense on its own. I never felt like there was a part of this book that I could just kind of extract in that way.

With Confluence, my first full length collection, there were clear sections divided by the seasons. It felt like I could extract one season out of that and make it into a chapbook. Confluence actually yielded several chapbooks. As I was building the full-length collection, I published those chapbooks. It was great as a confidence booster. I had a chapbook published in 2012 that contained a few of the poems that would go into Confluence. Confluence wasn't published until 2015. I had been working on that book since 2008. It gave me the confidence to continue. It made me feel thoroughly vetted, it helped me to find an audience.

For me, the chapbook is such an interesting and great project and has to do with how self-contained is the work? How much do you feel like you have to say? How expansive is the subject matter? It's like, do I have a 10 page essay in me or do I have a two page opinion piece?

Radha: Would you mind sharing the background for Aisle 228?

Sandra: Aisle 228 is a book of poems that is about the Chicago Cubs winning the 2016 World Series, going to baseball games with my father, and listening to baseball on the radio. Those are the broad themes. But the way it's structured, as a book of poems, it looks at the last 60 years of baseball history, since the 1960s until now. It looks at it through a subjective, almost memoir-like lens.

There are a lot of retellings in yarns but there is also a memoir-like quality. I looked at a lot of events that happened outside of my personal history and the Cubs, so if you're a baseball fan but not a Cubs fan, there are a lot of poems about other players, other teams. There are metaphors about baseball and life.

The project gave me the opportunity to turn some things on their end that we normally think of as intrinsic to poetry—to not be sentimental, not be nostalgic, to try to find a way to always create something new. I wanted to create quality poems and still incorporate some of those things, because they're a part of baseball in a way that our country can't get away from. It was a good craft exercise to try to write good poems that are also nostalgic or have some sentimental qualities.

Radha: Are there phrases or words associated with baseball that carry that sentiment?

Sandra: Yeah, I would say, legacy, myth. I’m writing poems about the past. Saying “Ebbets Field,” you're right there. It's a ballpark that was demolished in the 60s. The Brooklyn Dodgers are a thing of the past.

What I found so interesting is that I will do readings and there will be middle aged and old men coming up to me teary eyed after listening to these poems. They don't like poetry. They just feel their father coming back to them or their grandfather coming back to them, listening to the words. You're just dropping this trail of breadcrumbs.

Radha: The poems evoke nostalgic situations and yet the language draws us into, like you said, a baseball as a metaphor. I can't remember if it was Donald Hall or somebody else who suggested that baseball is one of the most poetic sports. How do you think about the way in which the poems open out into more than baseball?

Sandra: I've become familiar with a lot of sports literature magazines, and most of them will tell you that they get more baseball submissions than anything else. In fact, one has a contest which is anything but baseball—any other sport, just don't send us more baseball work.

But, back to your question, baseball really lends itself to metaphors, to bigger ideas. I grew up in a Christian household. If you think about the symmetry of the game—three batters and nine innings, three strikes and you’re out—there’s a lot of Christian symbolism there, the Trinity. At Wrigley Field, you sing three songs a game; you line up at the concession stand to receive your blessing; you wear special clothes to the game. You go there to see something larger than life, something that you can't do, perhaps superhuman; you're going for miracles. So, to me, there's just so much there that has to do with religion, spirituality.

Also, there’s the idea of the game always being there. I always think if I run errands, I'll miss the game. And I don't want to do that. But then I remember, this is baseball. There are 162 games; you're supposed to miss some; you're supposed to listen on the radio and it for it to be in the background while you're washing dishes. There’s the reliability of something being there for 200 days of the year, more if you include the postseason and spring training. And it’s the same people, it's a cast of characters you get to know.

In the book, there’s also the idea of aging. My father and some of the players in the poems are kind of stuck in amber, continuing to play out their roles even though they have changed. They’re dealing with new challenges, especially retirement. People can relate to that whether they’re sports fans or not.

Radha: Yeah, absolutely. There is a sense of ritual. Baseball is a touch point for so many people across demographics across the country. The poems in the book really do try to capture those dimensions, what baseball means to us as a culture. I really appreciate that.

How many years did it take to develop the manuscript start to finish? Was it seeded a long time ago and built up slowly? Or was it a really quick build?

Sandra: Kind of both. The entire arc of the book took a decade. It feels like an eternity. I was finishing Confluence. I had a publisher, and I started writing these poems. I knew maybe a year before Confluence found a home that this was the next project. At that point, I was a pretty young writer. I was not comfortable with having two projects going at once. I just knew it was starting to bubble up. Once I found a publisher for the other book, the poems just started coming. They were already in my head, for sure.

The seed of this book was probably planted when I was in high school. I wrote a poem about going to a Cubs–Braves playoff game with my father in 1998. And I lost that poem. I wrote it longhand. But I remembered a few phrases from it. I knew I wanted to recreate that poem.

The short part about it was that most of the poems, say about 75%, were written by the end of 2016. There were a couple of publishers who approached me and said, Okay, the Cubs just won the World Series. Let's do this now. But I just wasn't ready. It was missing about 15 poems. It's just not my style to write something up and just say, let's go with it. My process is really slow. So I didn't do it.

2013 to 2016 was when the bulk of the book was written. And then in 2017-2018, I wrote a few more poems. And from 2018 to 2022 I was just fiddling with it. Every three to six months I was going through, reading it again, changing tiny little things, maybe moving one poem around, and then I just kept sending it out.

It was extremely hard. Everybody says this—and everyone is valid for saying it—that it is really hard to find publishers for full-length collections of poetry. Totally true. But then when you throw in that it's about sports, it is a wrench, because a lot of the poetry publishers are not interested. Some poetry presses emailed me back and said, We have no idea how to approach this subject matter.

And then there were sports publishers that said, We love this, but we have no idea how to market poetry. Or we don't think it can make any money or whatever. And, trust me, I queried them all. I knew probably the landing spot was going to be a University Press. It just it took a long time to find the right one. I just had to keep putting it out there. Any place that I thought it could possibly have a shot, I sent. I think I got more and more desperate as it went along.

The funny thing is that there were a lot of people I knew, a lot of people I had encountered in readings, who really wanted to buy and read this book before it came out. And with that long runway of me talking about it on social media or doing readings, they were like, Tell me when it's out, I can't wait to buy it. So I knew there was an audience, but convincing a publisher that there is an audience is is a whole other thing.

As poets, if we try to look at our work objectively, as much as we can, we'll never get there. I got to a point where I said, This is a good book, someone should want to publish this. This is just as good as the things that I'm reading from this or that press. I was there for probably two years before it found a publisher. But it helped me continue to send it out.

Radha: Yeah. When you are getting all of those rejections, it’s difficult. You wonder, Is it me? Do I just need to try harder? Do I need to rethink the manuscript? So I appreciate how you focused on the quality of the work and developed a sense of its completeness as a book. Those are powerful touch points in the process that can keep us going over the long term. Otherwise it's a lot of noise.

What is your approach to revision?

Sandra: Revision is huge for me. I write a lot of very short poems, but my poems become shorter. What drew me to poetry to begin with was the economy of language, and how much can be delivered in so few words. After all these years, writing poems is still challenging. It's like a puzzle. I have this sense of deep play when I'm writing poems, because I love taking words out putting words back in trying to figure out if I'm saying anything in a poem twice, and getting rid of that.

Most of the poems that I wrote for this book were revised a few dozen times just in putting together the book. I met with some well known writers at residencies. I got to show them some of my work and one in particular said to me that a linear timeline for this book would be the hardest way to do it. I really respected this writer and so I tried for years to figure out another way to align the book. Maybe it was just a lack of creativity on my part, but I couldn't figure out any other way. So I started in the 1960s and I ended in 2016. Interspersed in that are some poems that are not on a timeline. There will be a poem about a specific game that happened in this specific year. And then there'll be a poem that is timeless—two people playing catch in a park.

At the end of the day, with revision, you really want to make sure in a book of poetry that every line of each poem is a poem. I'm a poet that works in lines, visually, to see what each line could mean. When I read my poems aloud, I read over the line, as if they're paragraphs. I like that duality, because I can have a visual line meaning and then I can also have a sound meaning that's different. I really looked at is every line of this book as a poem, and then the book itself as the larger, final poem. That kept me coming back to certain poems, even eight years after I wrote them and they were published in literary magazines. They still got changed.

I have a nine to five job, I work on other poems. I'd write essays, and put the manuscript away and not look at it for six months. I’d bring it out twice a year, three times a year. That really helped me to get that objectivity to see this is good, or this is glaringly not good, to make finishing touch revisions.

Radha: I appreciate the tone in these poems, because I think we have a misconception that poems have to be serious. In your poems, there's a sense of generosity and community.

Sandra: Thank you. For me, poetry is pleasure. It goes back to that sense of deep play. I'm not saying poetry can't be lots of other things, because it certainly is flexible enough to be all the different things that we want it to be. But for me, the reason I write it is because it's pleasurable. And so these poems hopefully will give the reader that feeling. I work a lot in sound. It scratches that deep brain itch, those sounds chiming against each other.

—

Find Sandra Marchetti on Twitter @sandrapoetry.

Upcoming Events / Poet to Poet Community

The Poets Circle: Drop-in Conversations

MAY: Flow & Modulation—On Variation

May 3, 6-7pm MT & May 17, 12-1pm MT

How do you invite variation into your work? How do the authors you admire work with the principle of variation?

JUNE: The Shapes of Things—On Form

June 7, 6-7pm MT & June 21, 12-1pm MT

How do we work with the principle of form in our poems? Is form a generative force, a guiding principle for revision, or both? Which authors or examples of form draw you most, right now?

You touch on everything that I wonder about, Radha. Thank you!

Good interview. I like the idea that a poem in a book might need to be “better” than in a lit mag.

I suppose it’s not surprising that poetry publishers are uninterested in sports, not even baseball, but it’s another measure, perhaps, of how out of touch they are. I suspect baseball has contributed as much to our language and thoughts as Shakespeare (example: Sandra’s use of the phrase “pepper the field”).

For those of us who experienced baseball deeply when young, it can be more than just nostalgia or sentiment, it’s part of our psyches. I’m reminded of this passage from Philip Roth’s essay “My Baseball Years” from 1973:

“As I remember it, news of two of the most cataclysmic public events of my childhood—the death of President Roosevelt and the bombing of Hiroshima—reached me while I was out playing ball.”

Now that baseball is no longer the national pastime, in the sense of occupying so many of the places where we exist, it’s not clear what, if anything, will replace it. Video games? Social media? Soccer? I think not.