From Fragments to ... Major Book Award!

Katherine Indermaur's collection I|I wins the Colorado Book Award

CONGRATULATIONS KATHERINE INDERMAUR—WINNER OF THE 2023 COLORADO BOOK AWARD IN POETRY!

In honor of her achievement, I’m re-sharing this insightful interview with her about the winning collection I|I.

Katherine attended a poetry manuscript class that I taught at Lighthouse Writers Workshop. When her manuscript was chosen for Seneca Review Books’ Deborah Tall Lyric Essay Book Prize, she wrote me: “I took your poetry manuscript course when I was trying so hard to figure out how to order the sequences in my book I|I. I loved your practical advice, and it really made publication possible for me. Thank you!”

About Katherine Indermaur and I|I

I|I, Katherine’s first full-length book, was selected as the winner of the 2022 Deborah Tall Lyric Essay Book Prize by Kazim Ali. She is also the author of two chapbooks, an editor for Sugar House Review, the recipient of prizes from Black Warrior Review and the Academy of American Poets, and was named runner-up in the 92Y’s 2020 Discovery Poetry Contest. Her writing has appeared in Ecotone, Frontier Poetry, New Delta Review, the Normal School, Seneca Review, and elsewhere. She is a graduate of Colorado State University's MFA program, and she lives in Fort Collins, Colorado with her husband and daughter.

Watch the video below, or keep scrolling to read the interview in text. To hear Katherine read excerpts from I|I, check out the video (I highly recommend it).

Special note: This interview discusses topics of self harm. Please take advantage of these resources (noted in the book) for information and support: National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 1-800-273-8255 or suicidepreventionlifeline.org; for body-repetitive behaviors, the TLC Foundation (bfrb.org) and the Picking Me Foundation (pickingme.org).

From Fragments to Whole

Radha: I’d love to start by asking you to describe the book. It's a bit different than your traditional poetry collection. It’s considered a serial lyric essay. For those of us who aren't familiar with that form, or maybe just aren't familiar enough to know that we actually have read books of this type, what does that mean—a serial lyric essay? And what does it mean to you specifically?

Katherine: The serial lyric essay is a form that in my mind lives between prose poetry and nonfiction. One of the roots of the word essay is to try. So it’s an attempt. The serial nature of the book is one in which on every page I'm attempting to approach the topic from a new angle. That attempt extends into the full length of the book.

A lot of people have actually read serial lyric essays without recognizing that they are doing so. It has become a more popular form, reaching a broader audience recently. For example, the author Maggie Nelson writes often in the lyric essay form. Bluets, a really popular book of hers, and The Argonauts could be considered lyric essay. The poet Heather Christle recently came out with a book called The Crying Book that does something similar to my book where she is engaging with the history, the politics, the idea of crying, intermixed with her own personal experience, places she's cried, reasons she's cried. And the idea of white women's tears being used for political gain and change.

There are elements of poetry in the book. Space on the page is important, words get broken up, sentence structure isn't always the organizing principle. But overall, it's written in prose paragraph. There's also a lot of interest in research. The book delves into mirrors and psychology around mirrors, so there are elements of both nonfiction and poetry. It’s the repetitive nature that makes it a serial lyric essay, I think.

Radha: It’s a gorgeous book. And I hope that many folks will be excited to experience the form for themselves. It makes sense that the thrust of the book is one of inquiry. It's highly thematic at the same time. Would you like to describe the primary inquiries and themes of the book? And where did those start for you?

Katherine: They started by happenstance, which I think happens to a lot of poets. I was in an MFA workshop, just writing poems for that workshop and sharing with my peers. Mirrors started to come up as symbols and objects a lot in my writing. I thought, I should delve into that more. Mirrors are interesting. I was curious. Who invented mirrors? When did mirrors become so ubiquitous? I knew for a while that they were very expensive, only fancy rich people in the West had them. What were experiences of mirrors in the East? I had so many questions about mirrors.

As I did some research, it occurred to me that part of the reason I was interested in mirrors is because they trigger, for me, symptoms of a skin picking disorder. Standing in front of a mirror is one of the ways that I get started picking my skin compulsively. I've had a very fraught relationship with mirrors. Over the years, I have gotten rid of a lot of mirrors. I have covered mirrors in my house on occasion, with scarves and things like that. So I've had a lot of personal experience with thinking about mirrors. The project just became this nexus of those two concerns.

Some of the themes include vision, the nature of vision of light, and how vision informs our psychology, how we think about ourselves. The book was an attempt (again, that word!) to heal, to think about healing and what that might look like, and how seeing offers people the opportunity to heal from the harm that seeing can cause. So there are attempts to bring the body into the book.

Radha: What a powerful symbol. In the book, it keeps opening up. Just as a mirror would literally reflect different angles, each of the pieces within the book does the work of a mirror. I appreciate the intellectual curiosity that can drive a project like this, drawing the emotional content right into that inquiry, as well. It’s not just an intellectual exercise; it's both the mind and the heart approaching these topics.

Folks who are listening and or seeing this interview will hear just how poetic this form can be. Even though it is considered lyric essay, it's it's very much in the space of poetry, drawing us into an imaginative experience. Parts of the lyric essay spill into one another, mirror one another, strongly.

How did you decide the structure of the book? How did the pieces come together as a whole? Did you start with the first fragments, working in chronological order?

Katherine: I love this question because I'm still wrapping my mind around how it came together. It was not easy. You were talking about how the fragments spill into each other, and reflect off each other. That made it very hard to structure the book. It was so unwieldy. And I've never written something this long before.

Initially, I did write it in discrete chunks. I thought, okay, this section is concerned with these things. And this section is concerned with these other things. And in this section, this is going to happen. That approach served the project for the period of time in which I was initially submitting excerpts for publication in literary magazines.

The pieces stood alone for the purpose of appearing in a magazine, for a reader who was just going to read that one excerpt. Once I sat down with all of those and started thinking about the book-length collection, I didn't know how to do that, how to think about structuring it.

Initially, I was doing a lot of research and taking a lot of notes. Those notes would spark questions and ideas, and then I would write a little bit beyond just the notes. And I kept revisiting those. I had a professor who encouraged me to try to find an arc through the book, which I didn't want to do too much because I felt like the fragmentary nature of the book would be stolen. I didn't want to falsely say “The end. Everything's fixed. Everything’s fine. I'm healed, nothing going wrong anymore.”

The arc in the book was very organic. I started to write a series of pieces that I call practices, they all start with the phrase of practice and then a colon, and they instruct the reader to do things outside of the realm of the book. I realized that I could use those as an organizing mechanism throughout the book. I could intersperse them, the reader would start to expect them and look for them. And I didn't think so much about like, Okay, this practice is talking about this. They are a reprieve from the research heavy portions of the book.

I also wanted to build up to an intense section—right at toward the very end of the book—that touches on self harm. I wanted the reader to feel prepared for that moment, to feel cared for in that moment. I knew that the reader was going to need to be prepared and then be lead out of that at the very end of the book.

Radha: I wanted to let the language linger, let it work on my brain. I appreciate this thoughtfulness you're describing in leading the reader through the territory of the book, knowing that there is something heavier, more difficult psychologically, in that arc, preparing the reader for that.

I think a lot of times, as we're trying to shape our collections, we focus too much on the strong notes, where the timpani and horns are going come in. We’re not as attentive to those moments where we let the reader settle a little bit or come back into their body in a different way. I think it's brilliant how you've used these variations in the text.

You said that the book was first published, in part, as a chapbook. How did that work within your overall process?

Katherine: I came up through this traditional approach to poetry publishing in which poets do chapbooks and then they do full-length books, and then sometimes they do more chapbooks— but a chapbook is a great first step leading up to a full-length book. I actually have another chapbook that I published that has not become part of a longer manuscript. It's a standalone thing.

At the time I started, I was working full time and finishing my MFA. I thought, if I'm going to finish this book, I need a goal. I needed an intermittent goal of the chapbook. I thought, if I can get to chapbook length and have that work, then maybe I have it in me to do a full-length version of this book. So I did that.

When I first was submitting that chapbook for publication, that was the entire project. I knew that my eventual goal was to continue working on it into a full-length book. I was still adding to the project. It was just a goal for me, because it was such a long work. I'd never written anything quite that long and didn't really know how to deal with something that long, even though it is in chunks. Plenty of times in revising the book, I had to move things around and move things around. It's not like, oh, this has to come before that.

So yeah, I was really lucky to have it last year. Last summer, the chapbook Facing the Mirror came out from Coast to Coast Press, which publishes genre-less or hybrid work. They have a journal as well.

Facing the Mirror was actually the title of the book when I submitted it as a full-length collection. And then we changed the title.

Radha: Titles are sometimes very tough. How did you land on the title I|I?

Katherine: It was a suggestion from the publisher, Seneca Review Books. Jeff Babbitt there has been great to work with. His work is another really good example of lyric essay. The publisher wanted to distance this version from the chapbook, which makes sense. This title was probably the third one that we landed on. The other two were excerpts of things that occurred in the book.

With I|I, I was initially concerned about people knowing how to say it. Would it be more confusing than intriguing? I also thought about search engine stuff. Would that vertical slash mess up searches? How it appears online? But I eventually came to the decision that it really suited the work. And we have a little note in the book itself, telling people how to say it. I appreciate that.

Radha: It sounds like you had a good working relationship with the publisher who was also the editor, right? It's really wonderful when you can have that kind of partnership in finishing a longer work.

To close out, what advice do you have for writers—whether or not they're working on a serial lyric essay? What do you wish you'd known earlier in the process?

Katherine: One of the best things that I learned in my MFA program was that, as a poet, you can do research for your poetry, and that that's okay. I came into grad school thinking the Muse had to come visit you, you have to be inspired. And then, you know, any revision work that you did had to just be on that page. Thankfully, grad school exploded that romantic idea for me.

I love to research things or work with other texts. I find that I do my best writing when I'm reading. Just little lines from poems inspire me. If I'm looking at a book and I think I see a word that's not there, that's really interesting. That'll spark something for me. So I’m constantly reading, even if it's not poetry, reviews of books, reports from Scientific American or something. Just following your curiosity.

I went to a reading several years ago, before the pandemic, before Ada Limón was our Poet Laureate of the US. She talked about how her writing process has never been to write every day, that she prefers to just take notes on things. Then maybe once a month, or every two months, she'll sit down and write a bunch of poems.

I love that process. I don't always sit down and write a bunch of poems but I think that process of constantly thinking as a writer and believing in the way that your brain works, in gathering information, following inspiration when you see it. The note-taking process for me takes a lot of pressure off, particularly while I'm taking care of my daughter. I can't always write a poem, but I can type a little phrase into my phone on my notes app.

—

Learn more about Katherine’s work at katherineindermaur.com.

Upcoming Events / Poet to Poet Community

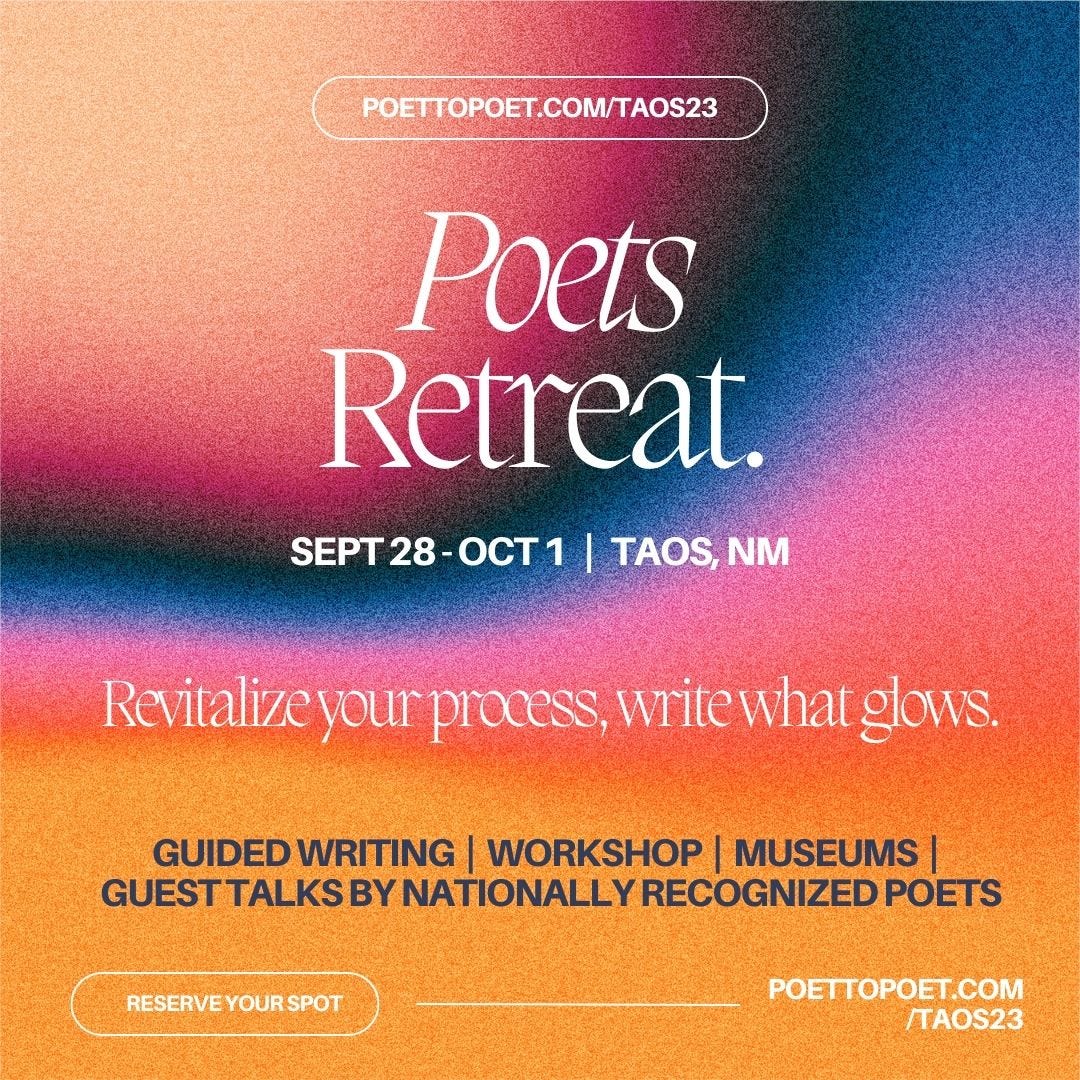

Fall 2023 Poets Retreat in Taos—only 6 spots left

This fall, join practicing poets for creative renewal in Taos, New Mexico. Enjoy three full days of guided writing, art tours, daily workshops, and guest author talks by nationally recognized poets. Space is limited. Learn more and reserve your spot at the link below.

The Poets Circle: Drop-in Conversations

JULY: Iteration—Toward Completion

July 5, 6-7pm MT & July 19, 12-1pm MT

How do you know when a poem or a book is done? What does "complete" mean?

AUGUST: What About Audience?

Aug 2, 6-7pm MT & Aug 16, 12-1pm MT

How much do we consider audience while we're writing? How much should we consider it? Should we consider it at all?