Hiding Beer in the Piano

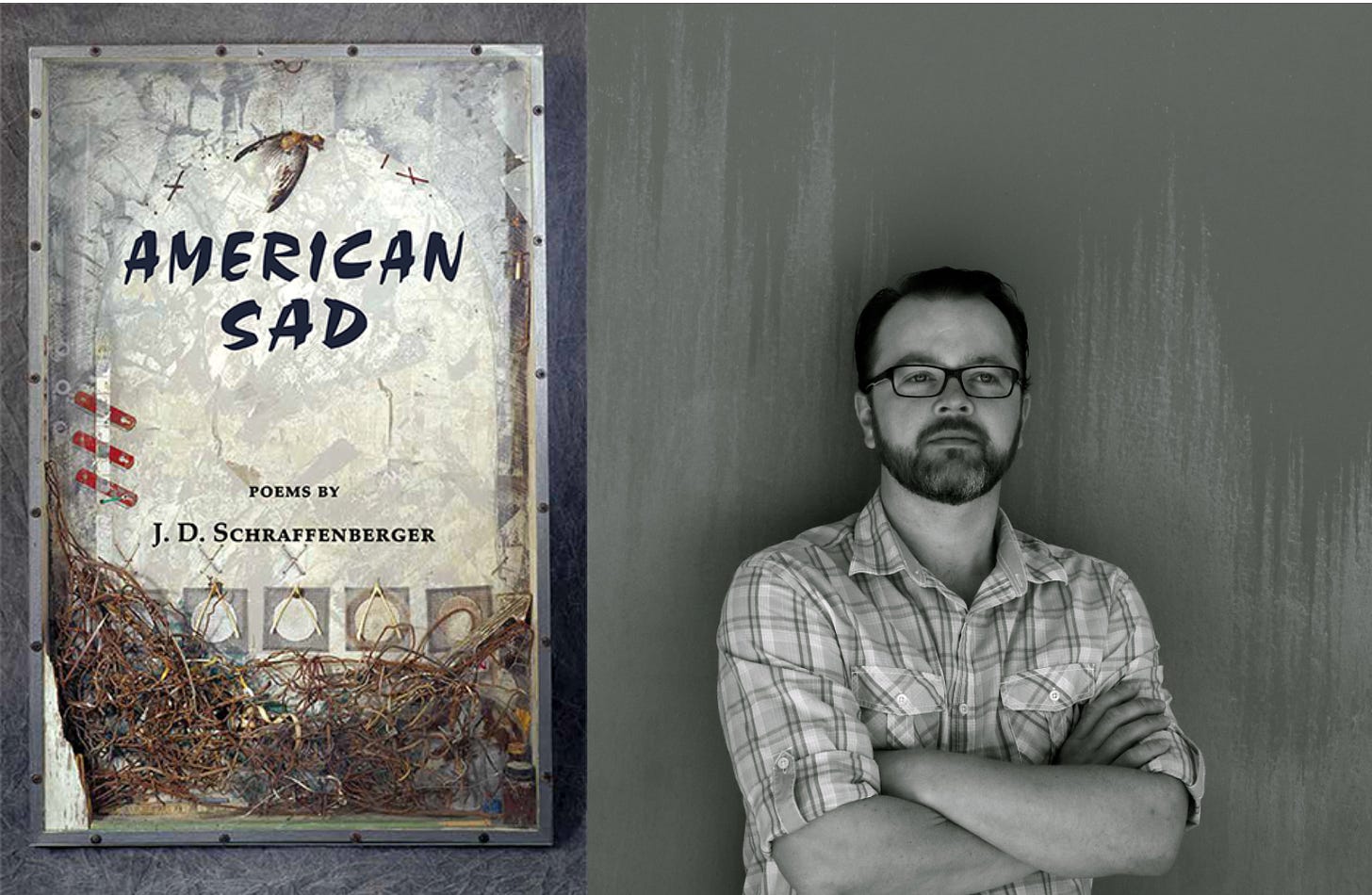

Poet J.D. Schraffenberger on the process behind his chapbook American Sad

HAPPY NEW YEAR, POETS! I’m thrilled to be back in the interviewer’s seat, nerding out on the process of poetry-book building in conversations like this one.

Coming soon: An announcement of Poet to Poet’s 2024 events, including new monthly lunch & learns on How to Publish Poetry.

Yours,

Radha

I recently had the pleasure of interviewing poet J. D. Schraffenberger about the process behind his latest chapbook, American Sad. We discussed how formal/stylistic choices allowed his subconscious to come forward in these lyric, beautifully “nightmarish” poems, many of which approach themes of trauma and intergenerational healing, plus:

What “American” sadness suggests

Tapping the unconscious while maintaining some control

Whitman’s “O,” and how poems make meaning and emotion through vowel sounds

Poetry as a “gift economy”—and advice on publishing

J. D. Schraffenberger is editor of the North American Review and professor of English at the University of Northern Iowa. He is the author of two books of poems, Saint Joe’s Passion and The Waxen Poor. His other work has appeared widely in magazines and anthologies, including Best of Brevity, Best Creative Nonfiction, Notre Dame Review, Poetry East, Prairie Schooner, and elsewhere.

Watch the video below, or keep scrolling to read the interview. To hear Jeremy read poems from American Sad, check out the video (I highly recommend it).

Hiding Beer in the Piano

Radha Marcum: Jeremy, welcome to Poet to Poet.

Jeremy Schraffenberger: Thank you so much, Radha. It’s a pleasure to be here. I want to say what a gift Poet to Poet is, because it is for people who often don't have community. We're writers. We're often introverts. Our very job description requires us to spend time alone inside of our own heads for a long period of time. And so it's nice to talk with other poets about what we're doing. So thank you for creating this community.

Radha: My pleasure. I'm really excited to talk about your new chapbook, American Sad. Because as a chapbook, I'd like to start with this question that I get a lot from students. And that question is: Should I try to publish a chapbook, first, or should I go for a full length book? Aside from the difference in length, how do you think about these choices in publishing?

Jeremy: Well, if you have a cohesive collection of poems that fits the chapbook length, that's fantastic. We should acknowledge the chapbook as a legitimate form in its own right. It's not inferior to a full collection; it's simply condensed. In fact, I would argue that it enhances the preciousness of the work. Having fewer poems and pages doesn't diminish its value; it just means there's a smaller quantity. The legitimacy of the chapbook was, in a way, solidified when Frank Bidart became a Pulitzer Prize finalist. That moment made us realize that being nominated for the Pulitzer Prize was within reach for chapbooks, providing them with a newfound legitimacy.

Personally, the difference between a chapbook and a full-length collection, beyond the formal constraint of page count, boils down to the intensity of the poems. I felt that the intensity in American Sad couldn't be sustained over a longer work. These poems, which I used to refer to as "nightmare poems," are somewhat surreal and intense. Putting that title on the cover might have discouraged potential readers, and I knew spending an extended period immersed in nightmares or intense memories wouldn't be sustainable. I wanted readers to visit this consciousness briefly and then be able to set it aside.

In contrast, my other collections were more project-based, often incorporating narrative elements. They honored both story and lyric, filling gaps in a broader dramatic context rather than continually exploring intense moments of surrealism or lyricism. The different imperatives of these approaches compelled me to continue with some projects and conclude others, such as this new chapbook. I'm curious to explore the distinctions between chapbooks and full collections, especially when considering project books, which, in a way, American Sad is as well—it's a project book in terms of technique and process rather than theme or narrative.

Radha: That's truly fascinating—what drives the cohesion in the work, whether it's narrative, technical aspects, craft, or form.

Jeremy: In non-project books, you often find all the poems cohering because it's the same poet, the same voice, the same aesthetic. It's like spending more time with the same person, and that's perfectly fine—actually, quite wonderful. I would venture to say most books follow this pattern, where there isn't another overarching frame or structure. However, what I've attempted with this book is slightly different. I tried to use a certain process and way of composing—some technical, formal choices—that make these poems distinct, make them cohere. It's more than just my own personal writing voice that's holding it together.

Radha: So, tell me about when and where the poems started. When did you realize you wanted the work to take the direction it did?

Jeremy: I anticipated this question and looked up the timeline. I began this project in late spring or early summer of 2019. At the start, I didn't have a clear idea if it would become a full collection or a chapbook. I just felt compelled to write in a specific way. Stylistically, my previous collections were quite controlled, with conscious and meticulous decision-making in every aspect. I wanted to break away from that and allow my unconscious mind to take the reins. I aimed to be out of control, not making conscious decisions but letting my consciousness guide the writing process. It was about discovering what was there, almost like sitting on a psychiatrist's couch and riffing on whatever came to mind.

The challenge then was to shape that raw material without losing the trace of the process. While these poems may appear wild, dreamlike, or even nightmarish, I went back and obsessively revised, not to eliminate the essence of the process but to refine it. It was a leap for me, as someone who likes control, to embrace vulnerability and allow whatever surfaced to be acknowledged and honored.

Radha: Absolutely. I love that notion. Poet Matthew Zapruder talks about recognizing a poem when there's something on the page that he doesn't understand—writing into the unconscious material. It's wonderful that this chapbook captures a crystallized version of that process for you.

Jeremy: When you engage in the process of allowing whatever comes, of relinquishing control and letting it emerge, and then acknowledging it as part of yourself, part of your psyche, and refraining from revising because it's unsettling. Allowing yourself to do that can lead you to dark and traumatic places, painful places. This book is titled American Sad, and I won't beat around the bush. However, I'm not a sad person in my daily life. This collection, I believe, contains an inherent human sadness.

Radha: The entire book opens up interior spaces, and the description includes the term "haunted." "Haunted" has that outside-inside feeling—a resonance with darkness both in the environment and within the human body. The poems beautifully bring together the scientific, familial, parental, and the worries, embodying them in consciousness and literally in the body. How did you think about describing these poems? Besides "haunted," how else might you characterize them, and what guided the thematic quality of the work?

Jeremy: First, thank you for your interpretation and descriptions. Your insights are thought-provoking. The poems introduce a theme: the idea of telling your sad story, suggesting that it's so sad it must be worth telling. These familiar scenes recurring in memory or family lore, which you can't shake off, embody the everyday, ordinary American sadness I described. While the book includes instances of suicide and attempted suicide, it's not revealing deep, personal emotional traumas. Instead, it carries a universal human sadness.

I often tell my students that what happens isn't always the point; it's the relationship to the memory of what happened. It's not even the relationship to what happened; it's the story you tell yourself about it. That reveals meaning and universality. As writers, we often perform on the page, presenting ourselves, and if we're too concerned about how we come off, we won't reach the real or the true. Art is about finding shared moments rather than emphasizing how we differ. Pain is universal, and writing about it creates a community in our humanity and the inevitability of pain. I'm circling around the question, but I hope it addresses some of what you asked.

Talking about experiences like those in the book is challenging, as the experience is in the poems. We can discuss the project, form, and stylistic differences, but if it's good poetry, it's challenging to talk about.

Radha: Let's delve into the title a bit more because it's intriguing. Poetry as we know it has always engaged with sadness, from the city laments in Mesopotamian traditions onward. So, a book about sadness may seem expected. However, adding "American" to the equation introduces a counter-cultural or even rebellious element. It challenges the typical narrative, and when you think about the phrase "American Sad," it raises questions about what an American sadness is.

Jeremy: You can relate it to the American Dream, the false promise that suggests constant upward mobility and the possibility of transcending your station. However, systemic barriers keep people from achieving that idealistic promise. It quickly becomes political when placed in conversation with the American Dream or the self-help ethos. American sadness persists because these promises are unattainable; they are lies and fictions, attractive but ultimately unrealizable.

Whitman comes to mind for me, with his exploration of sadness in the poem "O Me! O Life!" from Leaves of Grass. The word "O" has ancient roots in poetry, expressing sadness and lamentation. It's a beauty and terrible, an awful experience that's crucial to acknowledge.

Whitman's poetics, especially the idea of respiration, where you breathe in the world with sympathy and then breathe it out in pride, resonate with this book. It's about bringing the world into yourself, making it part of your body, and expressing it outwardly. It aligns with the creation of art, and the little spaces created in the book are like little "O's," resonating with the expression of the psyche. This is a pet theory of mine, and I hadn't planned on discussing it today, but it feels fitting when talking about sadness. Does any of this resonate with your work as a writer?

Radha: Absolutely. I recently taught a class called Toward Mystery, exploring how poets create meaning beyond conventional logic. We delved into the ways sound, particularly vowel sounds, contributes to meaning. Scientists highlight the significance of vowel sounds in conveying feeling tones, with "I" being bright and expressive, while "O" conveys darker emotions like sadness. Your theory aligns with this; it's interesting to see how sound and lyricism play a role in capturing emotions.

In a world in which we are more and more moving towards an ethos based in logic, a chapbook like American Sad is an invitation back to a deeper, fuller experience of what it means to be human.

Jeremy: That's fascinating, and it resonates with me. It's exciting to find these threads.

Radha: Let's talk about the choice to capitalize the beginning of every line.

Jeremy: It might seem old-fashioned, but there's a deliberate choice behind it. I noticed Robert Pinsky doing it, and Martha Solano influenced me too, especially with her serial syntax and parallelism. I wanted to capture a feeling of prayer or litany, a marked spot on the page reminiscent of an old typewriter carriage reaching a certain point. The capital letters served as a visual and mental marker, a rule that allowed me to focus on the writing process without additional decisions. It might seem arbitrary, but it played a vital role in maintaining the trance-like state and revealing how these poems came together.

Radha: Your choice to capitalize each line didn't strike me as arbitrary or archaic; rather, it felt like a counterweight to the end of each line, creating a balance. The typewriter image resonates with me; I started on a typewriter when I was six. I can still smell the scent of the ribbon—it takes me back.

Jeremy: Yeah, those moments of white-out and scrolling back …

Radha: I use a computer for composing now, but I keep my old typewriter as an artifact. I think these kinds of choices, such as capitalization, become part of the landscape of the specific body of work, capturing a particular time period and subject matter.

Jeremy: Absolutely, and I'm glad you acknowledge that. Writing new poems, I've retained what I learned from this process. While my earlier work was meticulous and controlled, this unfurling and relinquishing of control in American Sad was liberating. The new poems have a different look and feel, tapping into the wild and the unconscious while maintaining some control. It's a learning process, and I wrote many poems that didn't make it into this collection during the first year of experimenting with this mode.

In the poem “Piano," there's a scene where my daughter practices the piano. A few years ago, just before I started these poems, I visited my family, alone, driving our van, which was my family's van. My parents had my grandfather's old piano, and he was an autodidact who played by ear, only using the white keys. I decided to take that piano back with me on a nine-hour drive. Despite never having played before, I taught myself during a sabbatical. Now, I watch my daughter taking lessons on the same piano. Pianos appear throughout the collection, with this one carrying memories of my grandfather, an alcoholic, who would hide his beers in the piano, thinking we wouldn't find them.

Radha: The image of hiding beers in the piano is incredibly metaphorical, how we conceal our sadness or resort to drinking to bury it. The piano, as an instrument of beauty, is the voice that brings music into the world, much like poetry or the poet.

Jeremy: Exactly. The piano, unlike a guitar or flute, is larger than you, almost like a beast. It's something you sit at, not something you control easily. My grandfather's piano, now in my possession, has holes on the lid from a lock he used to prevent kids from playing it. This piano, once off-limits, now carries the weight of generations, and my daughter learning to play it feels like breaking free from that generational trauma.

Radha: What are who supported you most in doing this work? Did or do you work with mentors? Peers? How does that look for you?

Jeremy: I think a lot of people are in the same boat. You have writer friends that you've developed over years, going to graduate school, perhaps, or just a writing group. In my case, I met my wife in grad school, doing a PhD in Binghamton University. She's a novelist, but she's written poetry, too. She's always my first reader.

We often go on a writer's retreat to a cabin in Virginia, spending a week focused on our writing projects. This community is a blessing, knowing that I'm not writing in isolation. However, for years, I didn't submit these poems anywhere. I knew it wasn’t just therapy. I knew I was creating art, but I wasn't taking the next step to submit them for publication.

I wasn't scared. I get rejected all the time. Getting rejected is just like paying your taxes, you need to do it. It's part of the whole deal. Then I did start to submit the poems and some of them were publishing; it snowballed from there. I knew that I was going to send the chapbook to Main Street Rag press, which was who published the first batch of poems that I submitted. I felt confident that, “Alright, I know the editor thought these were worthy to share in the magazine.” And he was happy to accept the whole manuscript. But before that the poems were like places I would visit. Eventually, I started taking them more seriously as something to share with the larger reading community.

Radha: Your strategy of building on the poems accepted by a journal is interesting. It's a way of leveraging an existing connection and making a logical progression from individual poems to a chapbook or larger collection.

Jeremy: Absolutely. And for writers wondering what to do with their poems, I'd say not to hesitate in reaching out to editors who have published their work. While not every journal has a chapbook publishing arm, some do, and editors may offer valuable advice or connect you with someone who can help. It's all about fostering connections and being part of the supportive poetry community.

Radha: Poetry publishing can seem opaque, but there are nodes of generosity; it’s a landscape of connectedness where poets want to support one another. Building relationships with editors who resonate with your work and seeking advice from those who have published your work is a great way to go about it.

Jeremy: Absolutely. Poetry publishing may seem cold, but there's warmth in the relationships and connections we build within the community. It's essential to remember that poetry, in the best possible way, is essentially useless in a commercial sense. Poets aren't breaking the bank or getting six-figure book deals. The interests are not commercial. Even the most successful poets, publishing with major houses, don't receive large advances.

Poetry operates on the gift economy—our commerce is the gift we offer to readers. Poetry isn't about making money but sharing something meaningful. My chapbook is not going to make a bunch of money. That's not the point. The point was to give the gift of it to readers. That's what I like about poetry. I write other genres, too. But that makes me feel different about when I'm writing and publishing poetry.

So do reach out to people, because people who are into poetry are involved in the same commerce. They're also in the gift giving business.

—

Get a copy of American Sad at https://mainstreetragbookstore.com/product/american-sad-j-d-schraffenberger/

I left a lengthy comment on the video, but just to emphasize--what a rich, complex interview! Thanks so much for doing this one, Radha. Definitely worth further discussion.

Sean Singer's Substack today discloses his particular methodology, which is meticulous in other ways. I love this discussion, as we uncover multiple approaches to creating a collection. So glad to have this interview to broaden the discussion.