How Themes Emerge

Poet Rebecca Aronson discusses how her third collection, Anchor, emerged from scribbled notes to poems to manuscript

I recently had the pleasure of interviewing Rebecca Aronson about themes and poems in her third collection, Anchor, and how they came to be while she was working and parenting full time, plus caring for elderly parents.

Rebecca Aronson is the author of Anchor, published in 2022 by Orison Books, Ghost Child of the Atalanta Bloom, winner of the 2016 Orison Books poetry prize and winner of the 2019 Margaret Randall Book Award from the Albuquerque Museum Foundation, and Creature, Creature, winner of the Main-Traveled Roads Poetry Prize (2007). She has been a recipient of a Prairie Schooner Strousse Award, the Loft’s Speakeasy Poetry Prize, and a Tennessee Williams Scholarship to Sewanee. She is co-founder and host of Bad Mouth, a series of words and music. She teaches writing at CNM in Albuquerque.

Watch the video below, or keep scrolling to read the interview in text. To hear Rebecca read poems from Anchor, check out the video.

How Themes Emerge: From Scribbled Notes to Poems to Manuscript

Radha: Can you describe the book’s themes for us?

Rebecca: The themes of Anchor are loss, grappling with loss, and grief and mortality, and also memory, and parenting. And actually being parented as well. There's both ends of the parenting spectrum in there.

Radha: You mentioned earlier that, as you were writing this material, you wrote into the themes in a different way than you had in your previous collections. I'm curious, at what point did you think, Oh, I've got the start of a book here? How did the themes arise in your writing process?

Rebecca: I’ve always been a poet who just writes a poem at a time. My first two books were very much collections of some poems I wrote—not that there weren't thematic connections happening, because I think we all tend to be obsessed over the same sorts of things over periods of time. But they weren't quite coherent in the way that Anchor is.

Anchor arose when my my parents both were ailing my father had Parkinson’s. He was not yet diagnosed and he was falling a lot. I was flying from Albuquerque to Minnesota to be with my parents. And my mother had dementia at the same time. I was spending a lot of time in hospital rooms. Because my father was falling a lot, I started thinking about the force of gravity and realized we take it for granted, and I didn't really know what it was. So I started doing some reading. Carlo Rovelli’s, Seven Brief Lessons on Physics helped me understand it.

And at the same time, in maybe my more poet-y way, I was also picturing gravity as a kind of character. Like a sort of capricious God or maybe a mischievous bully. I was sitting in a hospital room while my dad slept on one of the visits towards the end of his life, and I started writing a letter to gravity. That was pretty unplanned. I just scribbled in my notebook, “dear gravity,” and then just went from there. That was the first of the “Dear Gravity” poems.

I kept doing that. I wrote probably 15 of them or so, and 10 of them ended up in one form or another in the book. They form the spine of the book. Once I realized that I had a bunch of these and that the other things I was writing all kind of spun from those letters, I began to realize that I might have a manuscript.

Radha: That’s so fascinating, the way that you took a phenomena and applied it to the themes of loss, grief, feeling our mortality—embodying that force in a character and then writing to that character. It’s interesting to see how that all develops in the mind of a poet like yourself. It’s a wonderful picture of how it can happen.

In the “Dear Gravity poems,” sound and imagery go back and forth in the epistolary (letter poem) form. The form holds a lot of potential. How many years did it take to develop the poems that became this manuscript?

Rebecca: I think of it as 2017 to 2020. But actually, I was probably a bit longer than that, because I know a few of the poems in the book are older than that, maybe from 2015 or so. So it was about five years total, but the "Dear Gravity” poems started in 2017. So the center of the manuscript didn't cohere until around 2017.

For me, that was super fast. I'm a slow, slow compiler, a slow writer. My first and second books came together much more slowly. It was somewhat accidental. I had the “Dear Gravity” poems, and other poems that I thought might fit, and I stuck them all in a Word document and just printed them out to see what was there.

I shocked myself because I didn't feel like I had been writing a lot, especially with working full time and parenting, and traveling during those years so frequently to Minnesota, I felt like I was never I never had time to read or write or do anything breathe. It shocked me to discover that I actually had all of these poem drafts, and that they all had threads that connected them. It was an unexpected delight in a pretty hard time to discover: Maybe there’s a book here.

Radha: So many poets that I know, myself included, are in the same boat—life is happening all around us. Time is so precious. It feels like we're not doing the writing that we should be doing. For me, that “should" comes into it. When you look back, how were you getting those poems done? What was your process? How did the process fit into life and all of your responsibilities?

Rebecca: Some of it was in hospital rooms, quick scribbling. When I was staying with parents to help out, it was just this notebook scribbling that I was doing. Two other things helped me get drafts done. I participate annually in one of these April poem-a-day groups. April's really a busy month. So I usually don't get 30 drafts. Most of the drafts are truly terrible. But I get the start of something. And that often gives me stuff to work on in the summer, when I'm not teaching generally.

Also I have a writing group at my college that I facilitate for students and anyone else, where we just get together and write once a week. Those drafts are super rough, they're not anything much. But often there's a spark there that might later turn into something. Those activities help keep me lightly tethered to writing during the busiest times of the school year. During the breaks—like every teacher—I try and put it all together, or mostly. Mostly I'm revising at that point.

Radha: I've had some similar experiences recently with producing the starts of what might be poems I want to work on, and breaking up that process of finishing them, working on them later. Whereas earlier in my writing journey, I had more time. So I would take something from start to finish, and then start the next poem, start to finish. It's wise to have this sort of rhythm, maybe doing a lot of generative work in one period, and then coming back later to see something's here, I want to work on this. I'm going take these drafts forward in this way, through the rest of the revision process. That seems infinitely wise.

Rebecca: It was totally accidental. To me, it's circumstantial.

Radha: But it works! And, like you said, you have a whole book to prove it, that it can work. And we can achieve a lot in this way.

How did you arrive at the book’s title? Did you have any working titles?

Rebecca: Surprisingly, I don't think I did. Anchor was the title that I came up with pretty much right when I realized that it was possibly a book. That was really unusual for me. Both of the previous books went through something like 15 or 16 titles. I just couldn't couldn't figure it out. With Anchor, there's an image in one of the dear gravity poems where I say that my father's legs, which are filled with fluid, were an anchor. I had that image in my head. Also, I was thinking of the stuff that grounds you in your life. It's not only gravity that keeps us down, but family—both from the child and the parent perspective. They're the anchors. It felt right, right away.

Radha: Anchor makes a lot of sense. It's a concise title. It embodies the primary force, the speaker’s meditation on gravity. So gravity is what makes the anchor work. Anchor is the thing that embodies the phenomena. It’s a great title.

I’m interested in your approach to form. The poems have different tonalities, different ways of approaching the subject matter. So I wonder if you might reflect a little bit for us on the way that you approached form?

Rebecca: So I often make for myself arbitrary constraints—just just to help me tame the chaos, it helps me to have a container to work within. And so that is probably most obvious in there's several not even sure how many there's several abecedarians in the book. That's a form that I use when I'm stuck. They're immensely fun.

With other poems, I make choices that you might not notice as a reader, and maybe aren't even there anymore. I often start with a syllable count per line to get me going in a rhythm. I don't write in meter, except for sort of accidentally for the most part, but I do like having a syllable count to help me fall into a rhythm. Often that goes away when I'm revising. With the “Dear Gravity” poems I was led by the epistolary voice, this idea of what does the letter sound like?

Radha: Do you have any advice for folks who are putting together collections? What do you wish you had known earlier? What are the some of the things that you wish you'd known earlier that you've applied in this this third collection?

Rebecca: I feel like the thing that I always am relearning and forgetting and that I wish I would remember is to give my poetry life more of my very scattered attention.

Both my first and second book took a very long time, not because I didn't have the poems, but because I couldn't conceive of how to put them together. I'm sure I'm not the only one who finds revision, really, really hard work. The poems always need more work. I had a really hard time getting the energy and the attention—and also good first readers—to help me move them into a state where I was really happy with them.

My advice, if I have any, is just give your writing life the time and the energy that it needs for it to be something. I feel like that's a bargain I'm always trying to make, and I struggle when things are falling off the table. I'm always trying to put writing back onto the table. But if I could advise my younger self, it would be to keep the writing on the table more.

Radha: That’s beautiful. I so appreciate this advice to to give our writing life the energy and attention it needs—and to give it that attention over time.

—

Find Rebecca Aronson on Facebook and learn more about her work at rebeccaaronsonpoetry.com

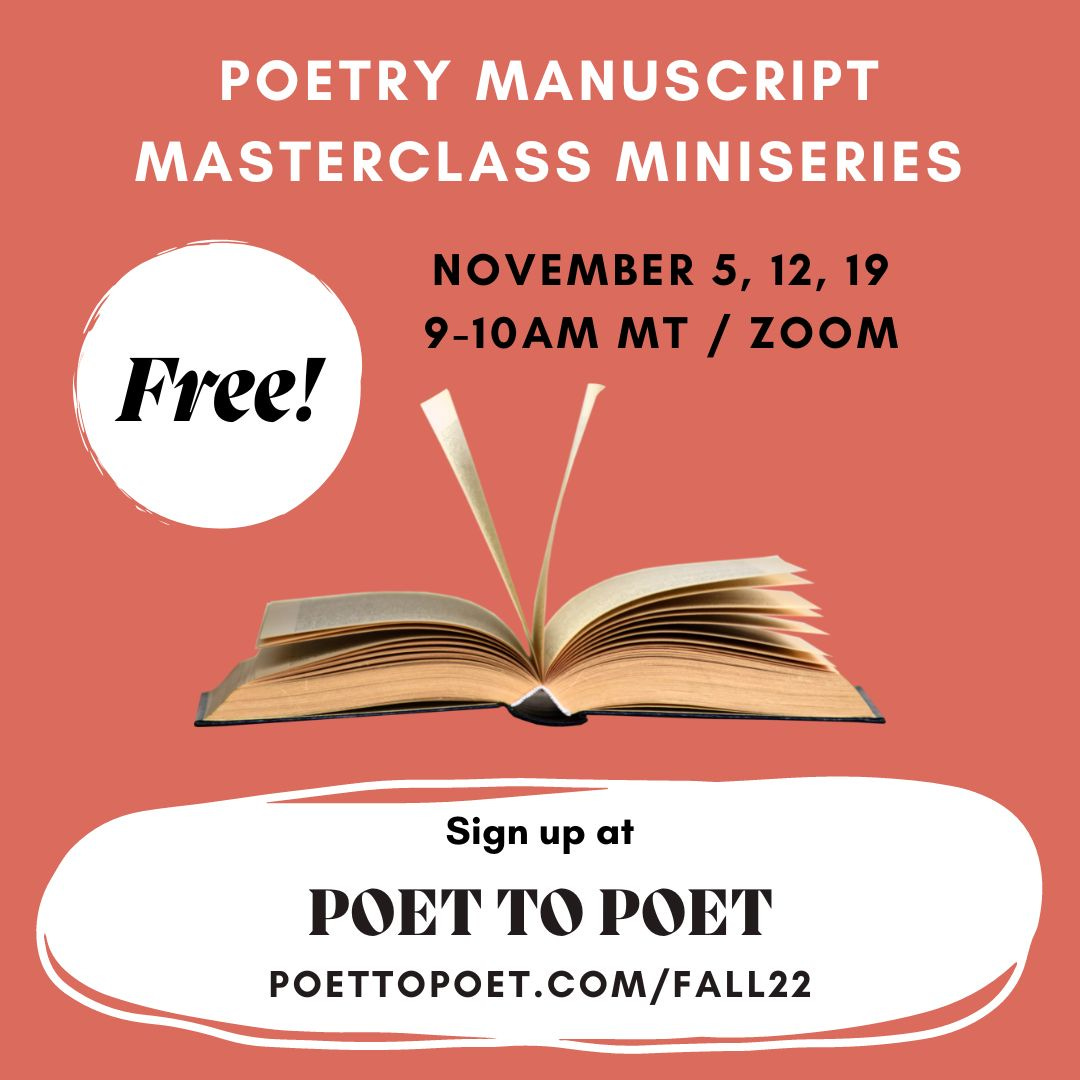

Do you have a stack of poems just waiting to be organized into a beautiful book? Or a manuscript that’s halfway there but needs … something? Learn the essential steps to creating a standout poetry manuscript in this free masterclass miniseries. Know where to start, what to do next, and when to start submitting.

This poetry manuscript masterclass mini series is for poets in any stage of creating a manuscript. Join for one class or for all three.

November 5: Anatomy of a Standout Poetry Manuscript

November 12: How to Sequence Poems

November 19: Common Mistakes—and How to Avoid Them

All classes take place on Zoom from 9-10am MT (8-9 PT, 10-11 CT, 11-12 ET)

Wonderful interview. I really enjoyed listening to her creative process and following how the collections came to be. Beautiful, sensitive poems. Thank you for sharing. Beverly George

I like the idea of gravity as a capricious god, even if we know that gravity is absolutely predictable (see NASA’s recent Dimorphos mission).

Maybe what makes gravity seem so capricious is that it appears to treat everyone differently, even treats species differently. Witness a cat leaping effortlessly and silently up onto a table, almost floating, a distance perhaps five times its height or more. Whereas without our machines we’re bound to earth, plus or minus a bit with a grunt, and we don’t always land on our feet.

I like the endings to the 3 poems she reads. No phony drama or rhetoric, they just calmly stop:

“The song I can almost recall the lyrics to.”

“But unable to recall what any of it is for.”

“Even as they land and settle in high branches.”

Seems as though there’s also a theme of unknowing or uncertainty in those endings.

And nice to hear how she honors the line break in the 3rd poem’s “dying / of laughter.”