Photo by Mikkel Frimer-Rasmussen on Unsplash

Hello dear poets. This week, I’m trying out a new kind of shorter post. Think of like food for poetic thought, an invitation to self inquiry around some part of the poem-making process, a game of What if … ?

Moth Migrations, How Poems Arrive

In Colorado right now, the miller moth migration is epic due to the extremely wet spring we’re having. The moths are everywhere. Outside. Inside. Moths keep fluttering out from behind photo frames, from linen closets, throw pillows. They’re everywhere, flitting in and out of my peripheral vision. The birds are going nuts over all this food.

Now you’re thinking this doesn’t have anything to do with writing poetry.

But it does. Because I think our best poems arrive just like these moths. Maybe not all poems, but often the juiciest and most necessary poems come out of our peripheral vision. We sense the poem while not looking directly at the subject matter.

Peripheral vision, or indirect vision, is vision as it occurs outside the point of fixation, i.e. away from the center of gaze or, when viewed at large angles, in (or out of) the "corner of one's eye". (Wikipedia)

A couple weeks ago I was working with a student on a new poem she had recently coaxed out of a series of images that had presented themselves to her. The draft had several potential directions, each equally compelling. But the essential why—the poem’s true direction—hadn’t revealed itself to her. We could both feel that why flitting in and out of peripheral vision.

She’s a visual artist, too, and she began to see how this poem—like a recent painting of hers—was challenging her to not look at the subject matter too directly, to avoid fixation. I thought this extremely wise.

What if our poems come from the periphery?

I know peripheral vision is essential to my process, although I might not have called it that before this season of moths and that conversation with my student. Mostly I know it because I’ve experienced the opposite: Focusing too hard, too soon on one possibility, aka tunnel vision—the result of my wanting to finish, wanting an outcome—narrows the poem’s potential.

But when I keep my vision wide, receptive, even a little blurry, poetry will arrive.

Upcoming Events / Poet to Poet Community

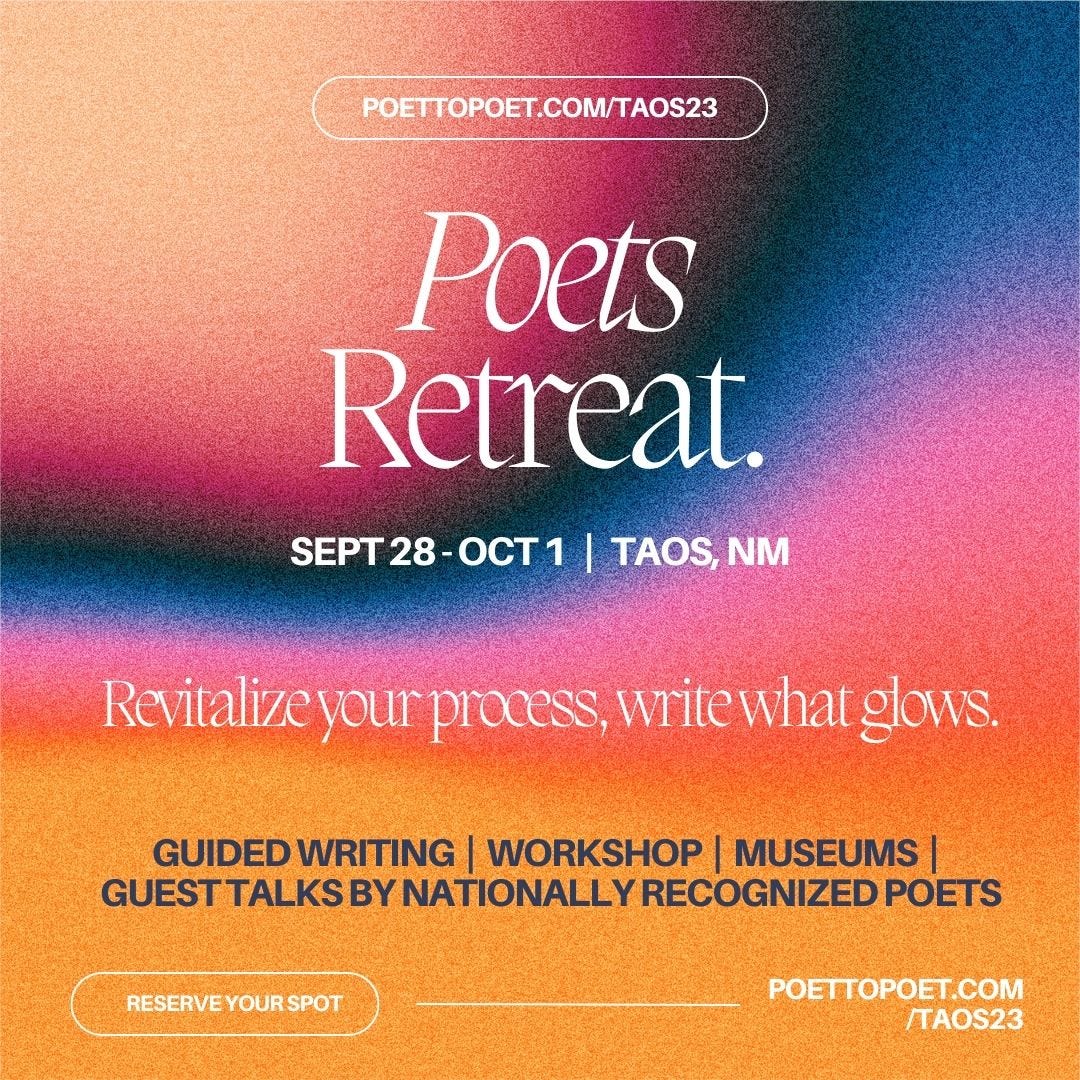

Fall 2023 Poets Retreat in Taos—just announced!

This fall, join practicing poets for creative renewal in Taos, New Mexico. Enjoy three full days of guided writing, art tours, daily workshops, and guest author talks by nationally recognized poets. Space is limited. Learn more and reserve your spot at the link below.

The Poets Circle: Drop-in Conversations

JUNE: The Shapes of Things—On Form

June 7, 6-7pm MT & June 21, 12-1pm MT

How do you work with the principle of form in your poems and in your manuscript? Is form a generative force, a guiding principle for revision, or both?

JULY: Iteration—Toward Completion

July 5, 6-7pm MT & July 19, 12-1pm MT

How do you know when a poem or a book is done? What does "complete" mean?

So interesting that you're writing about this topic now. It dovetails with my Creative Inspiration blog this week and with my experience with making both poetry and visual art. If we look too hard, too directly, or too focused, we narrow the field of discovery. I tried to address this in my poem "What is Found in Found Poetry" that arrived from the periphery. The periphery is where the surprises lay in wait. Thank you for the moth migration analogy--I love that image!

Yes. I like this and the metaphor of focus and periphery helps me. Neat post, Radha!