Photo by Jude Infantini on Unsplash

In art as in life, we’re mostly trained to spot what doesn’t fit and then to eliminate or smooth over those parts. But oddness is what enlivens poems. So what do you do with oddness when it shows up?

The strange image, comparison, angle in a poem often becomes “what glows”—the illusive insight we look for—suggests Matthew Zapruder in his memoir The Story of a Poem, about revising a poem and revising his life. In a nutshell, the book describes this process: First, welcome strangeness. Then trust and build around it.

In an interview recently, he offered some advice he got from poet Brenda Hillman:

“Revise toward strangeness.”

This runs counter to our typical thinking. I love that. At best, I do this. At worst, I don’t trust the strange parts of drafts, and I end up going along with (unconsciously usually) others’ patterns, e.g.

Smooth or sanitize the language.

Work a draft so that it mimics modes of “our moment.”

Squeeze a poem into a post-confessional stance (prevalent today).

Lean into prescribed formal structures.

Etc.

I know this for sure: Not trusting strangeness = poems that are DOA.

The case for strangeness in our poems

Maybe I spend too many hours buried in blasé communications work and conventional media, but my brain craves strangeness in poems. These days, the denser the oddness, the better.

Why? Poetry functioning at its best deliberately uncenters me. It puts me off balance so that what comes next (in the poem, in my mind, in life) is new. Strangeness becomes the “top of my head taken off” feeling Emily Dickinson described.

To write from (or toward) the odd or off-center places in our psyches might be a good way to start.

From there it gets trickier because not all strangeness is productive, not all experiments work. Still, I think we don’t help our poems when we are too quick to edit and let others convince us to edit.

I often find myself advocating for the strangest parts in a participant’s poem during workshops.

You may have a different threshold for strangeness. That’s OK. But if you’re looking for an excuse to write less conventionally, consider that many of us would much rather read a poem that risks audacious oddness than one that follows a warn path.

How to (or not to) embrace oddness

Unfortunately, workshopping can be one of the worst places to cultivate productive strangeness. Critiques often start from the question, “what works?”—in the most narrow sense.

To get beyond that, we need to see that each individual poem sets its own rules. The oddness that “works” in my poem will probably not work in yours, though our poems may share certain qualities.

Also, yes, there’s a balance to strike. Oddness requires choices to hold that oddness. In a way, strangeness demands consistency. (Examples: Arthur Sze’s wild juxtapositions in standard-appearing couplets. Brenda Hillman’s stuttering textual marks glued together with sonic resonance between words.) Those consistencies help readers trust the poems.

I think a lot about the useful tension between strangeness and consistency as I’m revising.

How do you handle strangeness in your work? Share in the comments.

Upcoming Events / Poet to Poet Community

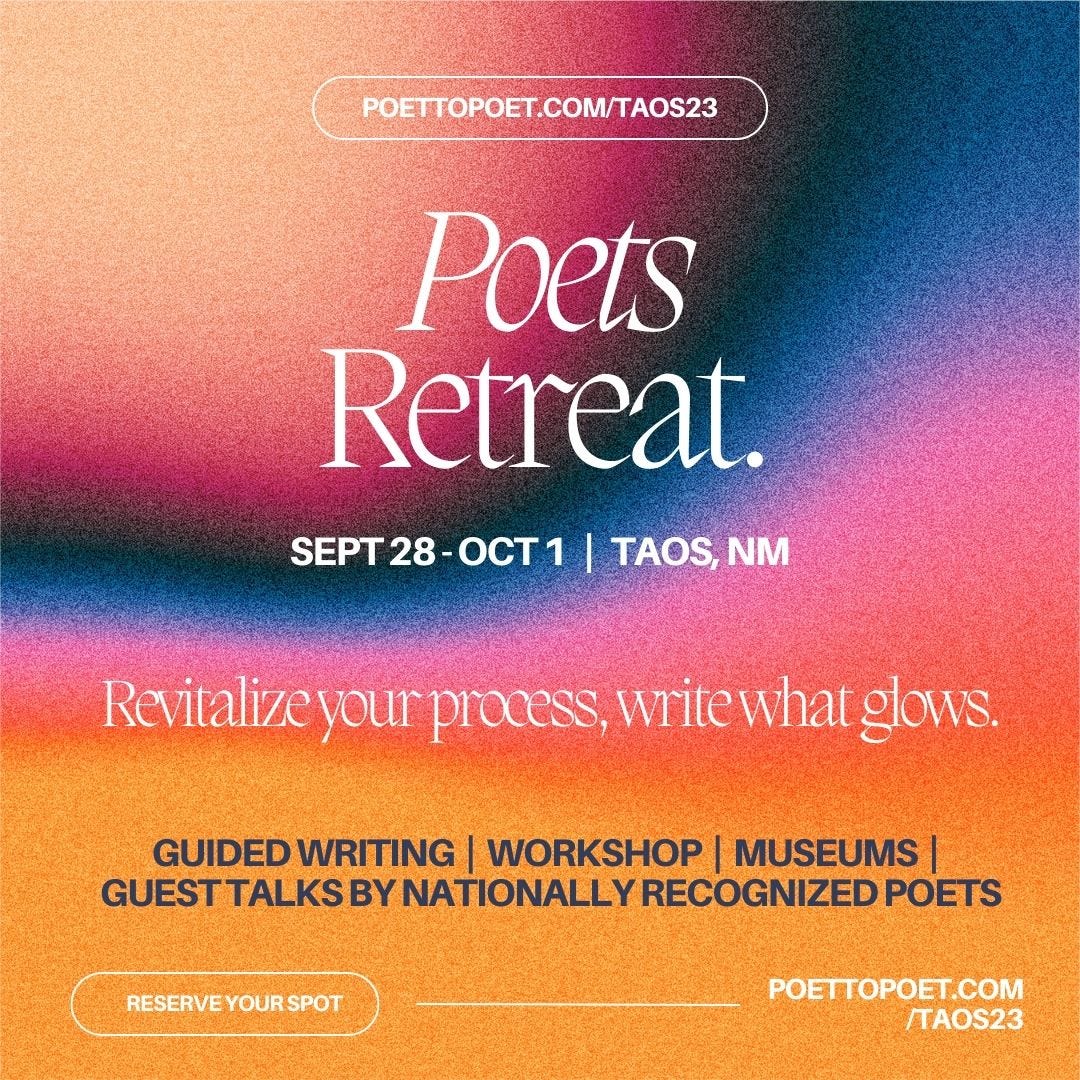

Fall 2023 Poets Retreat in Taos—only 6 spots left

This fall, join practicing poets for creative renewal in Taos, New Mexico. Enjoy three full days of guided writing, art tours, daily workshops, and guest author talks by nationally recognized poets. Space is limited. Learn more and reserve your spot at the link below.

The Poets Circle: Drop-in Conversations

JULY: Iteration—Toward Completion

July 5, 6-7pm MT & July 19, 12-1pm MT

How do you know when a poem or a book is done? What does "complete" mean?

AUGUST: What About Audience?

Aug 2, 6-7pm MT & Aug 16, 12-1pm MT

How much do we consider audience while we're writing? How much should we consider it? Should we consider it at all?

One of the stronger emotions is embarrassment. Poets don't use it. I have decided to let my poems be embarrassing.

Example (got pub'd in New Note Poetry):

I’m Not Waiting

I get out my waiting things

because I am waiting for God to arrive

and I like to wait.

I sit under a clock,

that wind-up saint of waiting.

I unbraid my hair then braid it up again.

I masturbate. I take a shower. I lie down to nap.

I go for a walk. At the park

dogs chase sticks and catch up to them,

then get distracted by dogs.

I can understand. I’m distracted, too.

I’m not waiting for a purpose or for digestion.

I’m not waiting for a stick or a stone.

I am waiting for God,

who walked the earth once,

walked back and forth over

what but for him had been all void.

Big void. One void. Any old void.

Back and forth over the earth

I walk, counting my steps

toward the awful conclusion of all my waiting.

I’m waiting you out, I tell God.

I’ve got your number. Or someday I will

have counted as high as your throne

and I will sit down just below it,

where your feet stretch out,

as under the clock I sit respectful and attentive,

while the hand chases a minute

from twelve to twelve.

To my waiting things I add a new stick,

a stick I picked up, tooth-marked and wet,

from among the running dogs.

I often think of lyrics, where oddness makes a song memorable. For example, just about anything by PJ Harvey (“I cast my iron knickers down”) or the B-52s (“Living in your own private Idaho (oh) / Underground like a wild potato”).

Or Bob Dylan: “Well, Shakespeare, he’s in the alley / With his pointed shoes and his bells”

That’s odd, but as soon as you hear it you see it.

Or this line: “The ghost of ’lectricity howls in the bones of her face”

That’s a strange, complex image, perhaps multiple images in the same line.