Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

I’ve been at LitFest at Lighthouse Writer’s Workshop this week—a revelatory week on many levels. I’m feeling a lot like I did when I wrote this piece last summer. How do you manage the grief you might encounter in liminal after-times?

—

Today I want to talk about an aspect of the writing process that we don’t often discuss. Maybe we don’t talk about it because it comes as such a surprise, because we’re expecting the opposite. I’m talking about the grief we feel when we’ve just completed something big, like a manuscript. Or the sadness we feel when leaving a conference we’ve anticipated and worked toward for a very long time.

This month, I sent out dozens of poems and received more acceptances from literary journals than in any other time period in my 20-plus years of submitting. I attended a conference that I’ve had on my wish list for at least a decade where I met inspiring peers and poets who have had more influence on my work than any others.

I should feel elated, right? It’s complicated. I feel full and empty at the same time. Some days, a new direction pulls at me. Other days I feel bereft. There are days that all I can do is walk the dog and scribble a few anemic lines in my notebook.

Why should this come as the surprise? After all, a poet’s primary job is to notice cycles—how things begin, become, come to fruition, and then decay. I know that a little or a lot of mourning is part of finishing the poem, the book, reaching the end of circumstances that brought forward the work as I navigate changes to my psyche, my health, the ecosystems in which I write.

Here are a few things I’ve learned about how to grieve and go on.

First, know the gap is nothing to be feared. Know there will be a next—a next publication, next book, next conference, etc. There will be.

The feeling you’re feeling is the natural exhaustion of having exerted yourself, gone all in. Celebrate that. It’s a sign of having done the work.

Work on other aspects of writing — submitting, networking, researching.

Let the done work be done. Let it sit. Don’t reopen documents and start tinkering just because. Don’t get jealous of the yesterday-you who sat in a trance working out every line.

Take a lot of space from your writing routines—your desk, your habits. Forget all of the pressure you normally put on yourself.

Try to avoid areas of public comparison like social media or even certain social groups you belong to if they are competitive (you know which ones these are). Take a step back from the fray.

Rest. Sleep. Avoid overstimulation. Make your job self-nourishment, like exercise and good food. Weed the garden. See that special exhibit at the art museum. Don’t just mind the gap. See it as a natural pause. Lean in. Enjoy the in-breath.

Give your mind good nourishment, too. Read for nothing more than interest. During gap times, I like learning from other disciplines like physics, art, or ecology. Infuse playlists with new music, listen attentively to whole albums.

If you must do something, do the poem pre-work. Walk and journal. Take a trip. A friend of mine writes on planes, another on busses. Set a very rough, not-to-soon date to return to your “work.” If you must write, try forms you wouldn’t normally (maybe short forms like tankas), with no pressure to produce anything you’d want to present to an audience.

Take a non-competitive group class. Let someone else guide you in the writing process. I took a class with my friend, prose writer Lisa Jones. I don’t usually write fiction, but it was such a joy to be led through the process of writing a short piece. It renewed my belief in the fluency I’ll tap when I do return to writing.

While we’re immersed in the process of creating, we can only see the shimmering mirage of completion on the horizon. It beckons. It smells like success—the success of seeing the work through, the possibility of that poem/project taking a more permanent shape out in the world.

There’s nothing wrong with mirages. There’s nothing wrong with that horizon. There’s nothing bad about feeling bummed when you finish something important to you. It’s just that we expect it to be otherwise. So why not expect it to feel like it does—uncentering and a little deflating? Why not lean into that gap? Go ahead. Grieve and breathe. And trust that your work, when you return, will be better for it.

How do you manage the grief of liminal times?

Upcoming Events / Poet to Poet Community

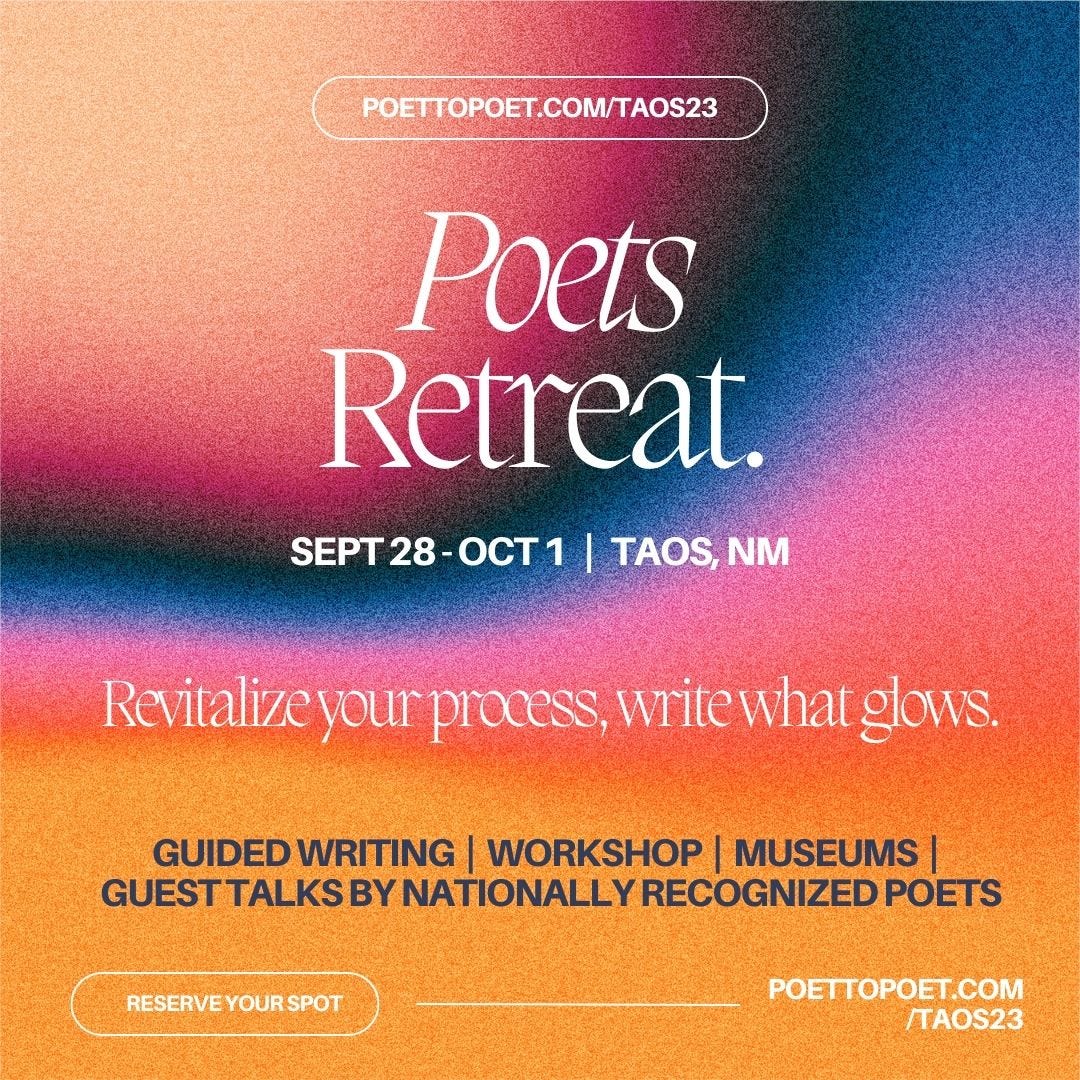

Fall 2023 Poets Retreat in Taos—just announced!

This fall, join practicing poets for creative renewal in Taos, New Mexico. Enjoy three full days of guided writing, art tours, daily workshops, and guest author talks by nationally recognized poets. Space is limited. Learn more and reserve your spot at the link below.

The Poets Circle: Drop-in Conversations

JUNE: The Shapes of Things—On Form

June 21, 12-1pm MT

How do you work with the principle of form in your poems and in your manuscript? Is form a generative force, a guiding principle for revision, or both?

JULY: Iteration—Toward Completion

July 5, 6-7pm MT & July 19, 12-1pm MT

How do you know when a poem or a book is done? What does "complete" mean?

I have various mental scripts that I have to run and re-run. They work. They don't work. I rejigger them. I forget them, and have to write a new script for the same situation. Some scripts:

I have written the poem. I honor it by offering it to the world. When or whether anyone else gets behind it (publishes it), is a separate thing.

Showing a poem to others helps give me perspective on the poem, whether or not any comment on it is made. Sometimes that change of perspective leads me to change the poem. It could also remind me how much I like it.

Not having a poem taken up (after many attempts) tells me that the poem is doing things other than what editors want to see. Maybe my kind of thing is out of fashion, or has yet to come into fashion. Editors really do want to publish what fits with what they already like.

Even published poems are little seen. Sometimes I think the poems that have been repeatedly rejected have had more readers than poems immediately accepted. Editors are readers too.

That’s a great topic. And yes, I think grief is the right word, although perhaps a grief without an easily located source, making it all the more baffling.

I’ve experienced what you describe more often with work than with my personal writing: the is-that-all-there-is or it-doesn’t-feel-the-way-I-thought-it-would feeling. And “knowing” that the feeling will eventually abate doesn’t help much either.

However, it’s possible this state reflects a ratcheting up of skills and ambition that’s occurred without our knowledge, an expansion of view, of possibility. That might be something to welcome, if so, or investigate to see what’s there.

But when does the feeling become actual writer’s block or even a period of depression? That would be a concern. And how would one know?

Some people may benefit from “overstimulation” (dancing? loud music?). Not sure I would be too prescriptive about activities during the in-between time, although some of those things have undoubtedly been useful to other poets. Just thinking about poems written after a museum visit, I can think of examples by Auden, Miller Williams, Rilke, and Jared Carter.