The much anticipated Oppenheimer biopic hit theaters yesterday. I’m looking forward to seeing it soon. Listening to a podcast recently, featuring current weapons laboratory scientists talking about being extras on the movie set, I had to press pause.

Just thinking about the movie gets me choked up. After all, it’s a story I’ve been “watching” my whole life.

My grandfather worked with Oppenheimer. He joined Project Y, the Los Alamos subproject of the Manhattan Project, in October 1943. My first poetry collection, Bloodline, grapples with that heavy legacy.

For years, Oppenheimer’s Dog was the working title of that manuscript. In fact, the poem “Oppenheimer’s Dog” was the first clue I had hit a thematic vein. The poem recalls a family story about Oppenheimer’s dog keeping my grandparents awake, barking. During the war, my grandparents lived across the street from the Oppenheimers.

Like almost all poems, it started with some literal thing. A family story. An actual barking dog. Then the dog’s bark took on metaphorical significance. It came to symbolize Oppenheimer’s regret, his eventual objection to further weapons development. And it held more personal, familial regrets—the regrets that reverberate through generations.

The book includes two other poems about J. Robert Oppenheimer. He appears in the long sequence poem “Project Y,” in which I return to New Mexico to explore that history with my children. And “Letter, 1954” a persona poem in the voice of Oppenheimer—an imagined lament directed at adversaries on the committee formed by the Atomic Energy Commission (influenced by McCarthyism) to discredit Oppenheimer.

While working on Bloodline, I came to see Oppenheimer not only a Promethean figure, but as an ethical/emotional stand-in for the psyches of other scientists, like my grandfather, who worked in absolute secrecy and silence.

I’ll never know how my grandfather felt about the use of atomic weapons during the war. I don’t know how he felt about atomic weapons development, in general. He took any regrets he might have had to his grave.

Do you have permission? What right do you have …?

At a recent reading, someone asked: “How did you decide it was OK to write about Oppenheimer, especially in his voice?” Implied there: What rights do we have to include a person’s story—or any part of history, for that matter—in a poem? It’s a fair question.

First, let me be clear, the poems aren’t historical records. They’re personal. They are clearly from the my perspective. I even included a note in the book stating that the poems are fictions based in my imagination.

Still, it’s very difficult to write about such complicated, emotionally loaded histories. What I learned in the process stayed with me and continues to play out in how I approach other topics.

Personal experience. I wanted the poems to be based, at least in part, on personal experience—of landscapes and places, particularly. (Frank O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died” comes to mind.) Even in the poem written in the voice of Oppenheimer, I used observed details from his home on Bathtub Row in Los Alamos. Those dandelions in the poem? I saw them there.

Factual details. Other details came from historical accounts that I used to back up personal experience and family stories. For example, I verified that the Oppenheimers did, in fact, have a dog by reading historical accounts.

Feeling. Emotions in the poems are my own, from experience—if not based in direct experience of a place or event, then based in a direct, empathetic response to history.

Negative capability. I tried to allow room for subject matters to be as complicated as they should be. Especially, I didn’t want the poems to become indictments. I did want the poems to suggest that, in many ways, we are all implicated. And that this history isn’t just history. We have an ongoing situation here.

Questions, more questions. I wanted the poems to open up territory rather than define something. I hoped the poems would point readers back to questions. What do we do with our culpability? Is it possible to lean into astonishing beauty while being aware of our extreme vulnerability in the face of apocalyptic technology (or climate change, for that matter)?

I’m not suggesting you follow these guidelines if you write about famous (or not famous) people or historical events, but these guardrails helped me to write and then to feel OK about presenting the poems to audiences who might expect them to be “true” (though I still find “truth” a highly suspect goal).

Oppenheimer’s voice, ours

Oppenheimer voiced his concerns and was damned for it. “He spent decades thinking about how to preserve civilization from technological dangers,” as this WSJ piece points out. His record was finally cleared posthumously last year.

A brilliant scientist, his perspectives were also deeply shaped by music and literature. After the successful denotation of the first atomic bomb at Trinity, he famously quoted from The Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” He frequently quoted other poetry, too.

In many ways, writing about Oppenheimer gave me a blueprint for how to approach other events and issues—the effects of radical climate shift, for example, in the American West, a place he loved so much.

Have you written about events or a person that required careful consideration of your responsibilities as a writer? What was your approach? Share your thoughts in the comments.

Upcoming Events / Poet to Poet Community

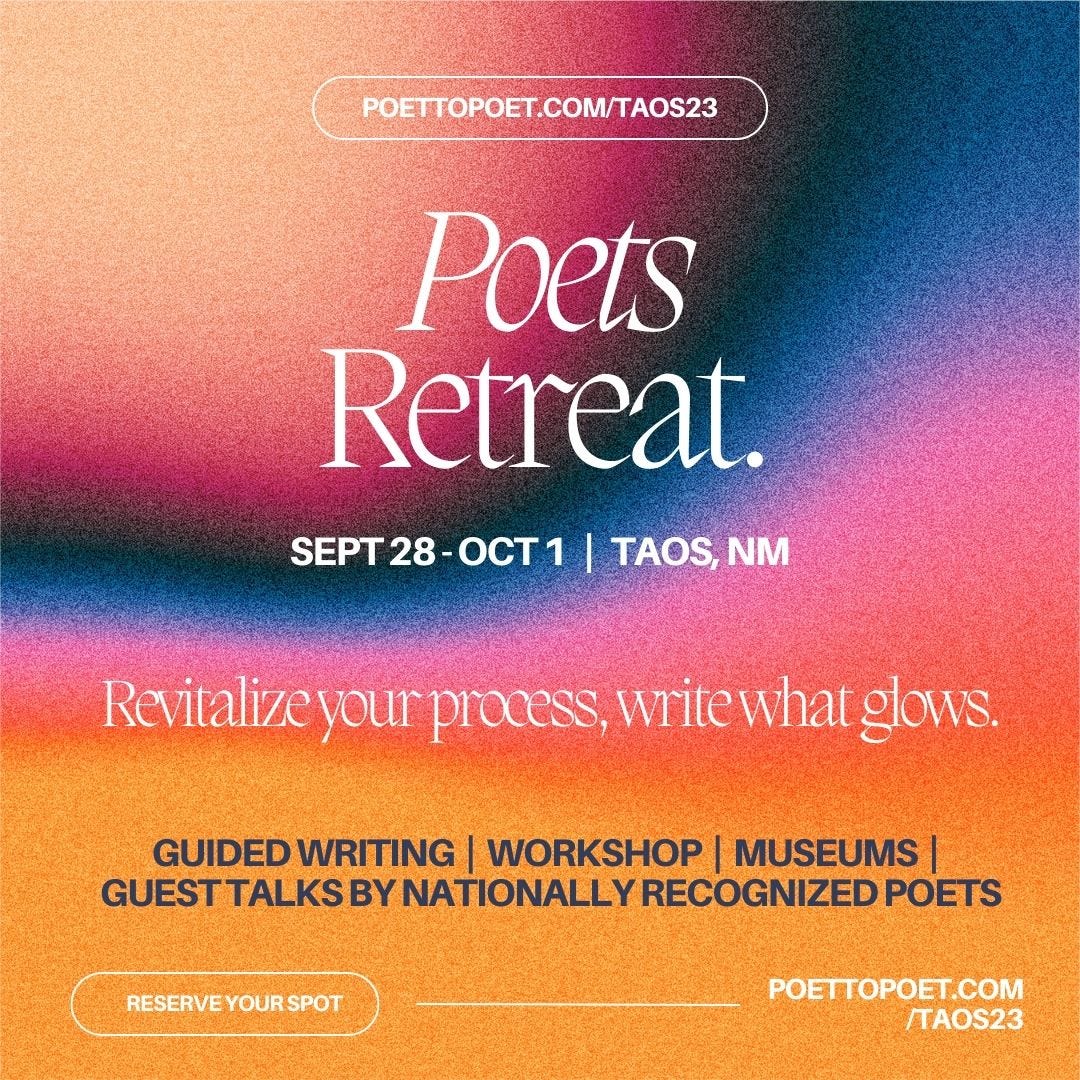

Fall 2023 Poets Retreat in Taos—only 5 spots left

This fall, join practicing poets for creative renewal in Taos, New Mexico. Enjoy three full days of guided writing, art tours, daily workshops, and guest author talks by nationally recognized poets. Space is limited. Learn more and reserve your spot at the link below.

The Poets Circle: Drop-in Conversations

AUGUST: What About Audience?

Aug 2, 6-7pm MT & Aug 16, 12-1pm MT

How much do we consider audience while we're writing? How much should we consider it? Should we consider it at all?

I really appreciate this post so much--it resonated with me for similar reasons, though my connections were not as direct as yours. I wrote about them here: https://www.wordsruntogether.com/2023/07/26/shockenheimer/ and my post might interest you as a fellow traveler in the shadow of the AEC. I suspect many of us are out there, hopefully wrestling with these ideas on paper. I will be curious to read anything you write about your experience with the film, though you might need to process for a while. Thank you for tackling these big topics. I'm ordering Bloodline now!

Radha, I love your book and find this discussion enlightening too about the personal and public and imaginary "things" you juggle there. Thank you. Oh and the Oppenheimer quotation from the Gita; that makes me tear-up, imagining what he felt to say that.