Poet Joanna Fuhrman discusses her seventh collection of poetry, Data Mind, which explores the internet's role in culture and personal experience.

We discussed:

The book's themes, a blend of humor and serious reflection on digital life

How poems explore algorithms, film, and gender

The internet as a lens for thinking about commodification, political changes, and contemporary issues like gun violence and women’s rights

Fuhrman’s experience as an editor at Hanging Loose Press—and her advice to poets

Joanna Fuhrman is an Assistant Teaching Professor in Creative Writing at Rutgers University and the author of seven books of poetry, including To a New Era (Hanging Loose Press, 2021) and Data Mind (Curbstone/Northwestern University Press, 2024). Fuhrman’s poems have appeared in Best American Poetry 2023, The Pushcart Prize anthology, The Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day, and The Slowdown podcast. She first published with Hanging Loose Press as a teenager and became a co-editor in 2022.

Watch the video below, or keep scrolling to read an excerpt from the interview. To hear Joanna read poems from Data Mind, check out the video.

Note: This conversation took place prior to the November election.

Poetry Predicted This

[Interview lightly edited for clarity.]

Radha: Data Mind is your seventh collection. Tell us a little bit about it.

Joanna: This is the first time I’ve written a themed book, which is a new approach for me. All of the poems in the collection explore the internet in various ways—what it means to live life online. As it says on the back cover—actually, let me read what’s written there. It’s a mix of what I wrote and what the publisher added; you know, a collaborative process.

"Joanna Fuhrman didn’t grow up online. Her generation entered the digital age as adults, optimistic about the possibilities it offered for community-building. In the alien landscape of the internet, they indeed found moments of joy and connection. But they also watched in anguish as what had been sold as a utopian space magnified the anti-democratic demons of necrocapitalism."

That’s the essence of the book’s themes. It also emphasizes that I’m an older person—52, Gen X—which shapes how I see the internet. Even though this isn’t an autobiographical book, my identity inevitably colors it. Being older, a woman, and Jewish all influence my perspective on the internet. These filters come through in the book, even though it’s not about my life. It’s comic and surreal at times, not confessional, but my voice and perspective are unmistakable.

Radha: I appreciate how you articulate the various lenses that inform your perspective. When I talk with poets developing a body of work, they’re often unclear about those lenses at first. Did you start with this project in mind, or did you discover it organically as you wrote?

Joanna: I didn’t set out to write a book about the internet—I was just writing poems, and the word "algorithm" kept surfacing. At the time, I was writing in a kind of mad, late-night state, typing random thoughts on my phone while trying not to wake my husband. Later, I’d look at what I’d written and realize it was all about digital life.

This started before the pandemic, but even then, I must’ve felt isolated and consumed by the internet. As the book progressed, I became more intentional. I started asking, “What does writing about the internet mean to me?” One angle I explored was the internet as a repository of the past, like looking at old films through the lens of digital life.

I also began considering political dimensions—how the internet has transformed us politically. Issues like gun violence and abortion came to mind, along with broader questions about how commodification shapes us. I’m not always sure what’s the lens and what’s being observed, but I wanted to weave in these contemporary issues.

Gender became a big theme too. The internet is a deeply gendered space, and I think it reflects and intensifies the gender divides we see in the world—like the growing gap between how women and men vote. A lot of that, I think, is shaped by the internet.

That said, the book isn’t moralistic. It’s not one of those essays declaring the internet is ruining us and urging everyone to unplug. It’s about having fun online too—it’s not doom and gloom. I wanted to explore all of it, from the absurd to the profound.

Radha: Right, well, I think that’s an important point. While other genres might approach these issues, events, or the intersections of internet experiences in a more intellectual or analytical way, poetry provides a different space for exploring and thinking about them.

Tell us a little about the organizing principles of the book. These are predominantly prose poems, right? How did you go about shaping them into a complete collection?

Joanna: Yes, they’re all prose poems. The book went through a lot of changes over time. Initially, I had this idea of creating a collection without sections—a continuous onslaught of dense poems—since I’d never written a book like that before. But as I worked on organizing it, I found that approach too overwhelming. So I decided to introduce sections and divided the poems thematically.

For example, I grouped poems about women into a section called “The Pink Internet” and poems about film into a section called “The Matrix.” However, an outside (anonymous) reader provided feedback that made me rethink things. They felt the film section didn’t quite fit and suggested the titled sections made the book feel too compartmentalized, with each section seeming overly distinct. They also suggested incorporating more internet language, which I really liked.

Taking that feedback, I reconceptualized the book. I added poetic “memes” as dividers—short pieces with lines from the poems—to give the book more of the texture of the internet. These memes also serve as a way to hint at the themes without being overly definitive, creating more permeable boundaries between sections.

The book does follow a loose progression. Early poems focus on the optimism and pleasure of discovering the internet, while later poems delve into its physical, sociological, psychological, and political consequences. The reader is taken on a journey that becomes darker and more complex.

That said, I’m conflicted about where the book ultimately ends up. I finished it during a time when it felt like Trump might win re-election [in 2020], and the conclusion reflects that anxiety. Even if that specific fear has shifted, our democracy still feels fragile, and our culture continues to struggle. So while the book ends somewhere, I hope it’s not a final destination. I think part of what I’m exploring is the idea that we should always keep reimagining what’s possible.

Radha: The way you describe that arc, and the process of discovering it, ties back to what you mentioned earlier about your particular experience of the internet—not growing up with it, but being there at its inception as it became part of culture, riding that train all the way to the present moment and the disillusionment that can come with that.

Joanna: But the crazy thing is, I don’t actually feel that disillusioned. The structure of a linear narrative suggests a progression—you start here and end up there—but real life is much messier. Things are mixed up, happening simultaneously. I didn’t write the poems in order, and even though the book is arranged to follow that arc, I don’t necessarily feel that way every day. Some days, I still feel optimistic about the internet.

Radha: That’s one of the beautiful things about this book—and other poetry books I love. The ending doesn’t feel like a definitive closure. Instead, it invites readers to go back and re-experience the beginning, holding the whole journey in their minds at once. A poetry book can take you on a journey while also allowing those different parts of the journey to exist simultaneously in the reader’s experience.

Joanna: That’s interesting, and I think it’s true. What I love is how poems can change meaning as the world around us shifts. One poem, for example, explores the relationship between dance and political protest. Its meaning feels different now than it did when I wrote it, and that evolving context is part of what keeps poetry alive.

Radha: Poetry allows associative leaps that mirror the slipperiness of subject matter on the internet—you’re reading one thing, and then you rabbit-hole into the next. In a way, the internet and poetry rhyme with each other.

Joanna: Yeah, totally. I actually wrote an essay, which I still haven’t placed, about how poetry predicted the internet. It explores how the qualities I love in poetry are the same ones that define the internet.

Radha: Tell us about your work for Hanging Loose Press. You’re an editor now, correct?

Joanna: We publish two magazines and six books a year, along with hosting events—it’s a lot! Most of the books we publish come out of the magazine. We start by publishing poets in the magazine, and if we fall in love with their work, we’ll go on to publish their books. That’s how it happened with me and my book.

I published several poems in the magazine during high school and college. Then, when I was an undergraduate, Bob Hershon had lunch with me. I’d sent him a poem that had been published in The New York Times—I was so excited about it—and he wrote back, inviting me to meet him in New York. At that lunch, Bob and the other editors expressed interest in a book from me. It took me a while, but after finishing grad school, I gave them a manuscript, and that became my first book.

This was a very gradual relationship, which I think is important for people to hear. I wasn’t in a rush to produce a book as soon as they asked; I needed more time. Even so, looking back, I sometimes wonder if I should have waited longer before publishing my first book. It’s a fine book, but I think my later books are stronger.

Radha: Well, I think it’s great that you took the opportunity when it came. Often, I tell writers I work with to think of choosing a press as finding a community to join, rather than just focusing on who will promote them or make them a big success. It’s about finding a chorus of voices you want to be part of. In your case, you were already part of that chorus through your individual poems, and it naturally grew into a deeper relationship.

Joanna: Yes, that’s a nice way of putting it. I love the idea of books being part of a community, especially since my work isn’t the most mainstream. Knowing there’s a specific audience for it means a lot to me. That said, things are constantly evolving. As Julianna Spahr recently described it in an essay, it sometimes feels like “Scotch tape poetics”—we’re all just trying to hold things together, especially with challenges like distribution issues at SPD.

Radha: I like that phrase—“Scotch tape poetics.” It’s such a good metaphor, especially for the challenges of keeping smaller presses and less conventional work afloat. Speaking of which, can we talk about what you look for in submissions? Hanging Loose has a distinct approach to selecting work, right?

Joanna: We do. While most of our books come from poets we’ve published in the magazine, we also have a couple of book prizes: a translation prize and a newer Founders Prize. For the Founders Prize, we read manuscripts nominated by people we admire, and the process is anonymous. For example, the most recent winner stood out because of the range in their work. The voice was consistent, but the poems explored a variety of themes and styles, showing a willingness to experiment. That kind of range is exciting to us.

Radha: That’s such good insight, especially for writers who worry about including varied pieces in their manuscripts. Many of them hold back or edit out the more experimental work, but sometimes that variety is exactly what editors want to see.

Joanna: Exactly. Of course, every press has its own preferences, but I personally enjoy work that’s open and surprising. I dislike poems that feel too closed, where you can predict exactly how they’ll end—it’s like a wind-up toy that spins down in an expected way. But among our editorial team of four, we each have different tastes, so there’s a balance.

One thing we all agree on is the importance of voice. It’s a bit amorphous, but we gravitate toward poems where you can really hear a distinct speaker. Another common issue we notice is overwriting—poems that take 10 lines to say what could be expressed in one. Concision is key, as is attention to sound and music.

Radha: That’s valuable advice. It’s about being precise, deliberate, and picky about what stays on the page. Reading work aloud is essential—it’s often the only way to ensure that the voice comes through clearly.

Joanna: Absolutely. I can’t imagine writing without reading things aloud at every step of the way. Even if I initially jot things down quickly—like on my phone in the middle of the night—eventually, I have to hear it to make it work.

—

Learn more about Joanna’s work at joannafuhrman.com.

Upcoming Events & Workshops

How to Publish Poetry — Lunch & Learn (Virtual)

Are you working on a full-length poetry manuscript or chapbook, or building a portfolio of journal publications? Learn how to work smarter and overcome common obstacles to getting published during these monthly sessions in 2024. Jump in any time. Our LAST session is December 4th. Get a free guest pass.

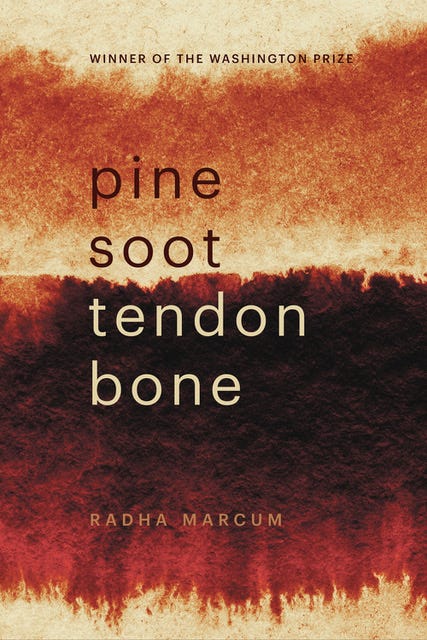

Pine Soot Tendon Bone

"Radha Marcum writes unflinchingly and with a rare synthesis of lyric and scientific intelligence, investigating just what it is to exist with consciousness now.” —Carol Moldaw, author of Beauty Refracted