Should We All Write Project Books?

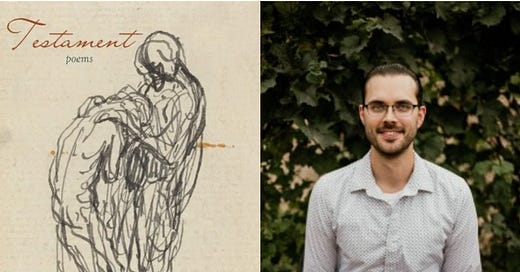

Luke Hankins, poet and editor of Orison Books, reflects on his latest book, Testament, plus shares advice on poetry manuscripts.

I recently had the pleasure of interviewing Luke Hankins about his latest book of poems, Testament, a chapbook from Texas Review Press.

We discussed:

The choice to stay at a chapbook-length work vs. pursuing a full-length collection

Striking a balance between contemplating internal perspectives and engaging with external issues in poems

Luke’s approach to accumulating a book-length work through a process of discovery vs. the “project book” approach

Trends in manuscript submissions and advice for poets—Luke’s perspective as editor of Orison books

Luke Hankins is the author of two full-length poetry collections, Radiant Obstacles and Weak Devotions, as well as, most recently, a chapbook called Testament, released by Texas Review Press in 2023. He is also the author of a collection of essays, The Work of Creation, and volume of his translations from the French of Stella Vinitchi Radulescu, A Cry in the Snow & Other Poems. Hankins is the founder and editor of Orison Books, a non-profit literary press focused on the life of the spirit from a broad and inclusive range of perspectives.

Watch the video below, or keep scrolling to read the interview. To hear Luke read poems from Testament, check out the video.

Process of Discovery vs. The “Project Book”

Radha Marcum: I’d love to start with a question that I get a lot from my students, which is: Should I try to publish a chapbook or go for it the full-length book? Aside from the difference in length, how do you think about these two choices in publishing? And specifically with this chapbook?

Luke Hankins: There’s no right or wrong answer. My chapbook trajectory is a little different than the more standard process, in which you publish a chapbook as your first publication and then, eventually, that chapbook ends up as part of your first full-length book. That didn't happen for me, I published two full-length books, and only now I'm publishing my first chapbook.

For my first two books, I had a larger backlog of work. It took many, many years to get the first book published, which is typical. By the time I published it, I had a significant number of newer poems—a solid percentage toward a second collection.

When my second book, Radiant Obstacles, came out, I had less of a backlog. I'm a rather slow writer, so I was slowly writing new poems. At some point, I started to feel like they were speaking to one another, that they were doing something together—that they were more than the sum of their parts. I started thinking of that small batch of poems as a chapbook, rather than rushing to try to produce poems for a full-length collection. I decided to be patient with my writing process.

Radha: That resonates with me—the sense you get that, yes, these aren't just a pile of poems, they are starting to speak to one another. Were there certain themes that emerged very early? How did the poems start talking to one another? Did that happen through thematic content, topics, motifs?

Luke: It’s very obviously interior facing work. I've always been the type of person who is introspective, I suppose, asking philosophical and psychological questions, addressing my experience of being in the world. I think, over time, I have tried, somewhat intentionally, to turn my gaze outward more. I’ve tried to balance the inward gaze and the outward gaze a little more in the poems.

Testament combines some of my long-standing themes—theological and philosophical musings and questions—but also looks outwards at social/political events and issues that are contemporary, that implicate a broader landscape than just the self—gun violence and racism and far-right politics. They may show up in quieter ways in some of these poems, but they're present.

Radha: It's interesting how those issues and and themes that you mentioned come into the poems, into that contemplative perspective. You don’t see that coming in some poems; for example, a shooter on the evening news.

Luke: That’s often when I feel a poem is most successful, when it leads me somewhere unexpected, as if the poem has a will and an intention of its own, making connections in the subconscious. That is the zone you want to be in as a poet. Right? That's one of the things poetry is so good for. I love reading poems that I imagine poets had a similar experience of discovery in the composition of the poem.

Radha: I really appreciate that perspective. I think a lot of contemporary poets might feel pressured to look at issues of because they are so prominent in our environment on a daily basis. In these poems, you arrive there—I don't want to say accidentally, because I don't think it's accidental. When you encountered that kind of moment in a poem, were you tempted to back away? Or did you recognize it immediately as fitting within the scope of what you want poetry to do?

Luke: I had a feeling of recognition this was where the poem was supposed to go. Part of this, for me, is just disposition. I'm not the type of poet who can give myself assignments. There are amazing poets out there who write what I might call project manuscripts—poems written intentionally about one topic, such as a historical person or event or, say, gun violence.

I don't produce results or worthwhile results when I try to do that with poetry. So for me, if it's going to happen, it has to happen in an organic way. I want to be attuned to what's happening in the world. If I'm successful in doing that and maintaining a sense of empathy for the types of suffering people are experiencing in the world, then those issues ought to show up in my poems. It feels right when they do. They don't show up in every poem, and I don't think they have to, but I'm glad that they show up to balance that inward and outward gaze.

Are you able to write? Like, give yourself sort of assignments topical assignments? In terms of writing?

Radha: Hmm. This is a question I get particularly from folks who are interested in the idea of a book. If themes are expected by editors, shouldn't we be all be writing project books?

Luke: I do feel that a book needs themes, it needs to feel like a cohesive whole. But really clear project manuscripts have become popular in a way that they weren’t in earlier decades. I look back, say, to the mid to late 20th century, and a lot of the most famous poets were publishing books that were collections of the various poems they'd written. Not that they don't have thematic and stylistic connections, but they weren’t all in the voice of Abraham Lincoln … Have you noticed that sort of shift as well?

Radha: Oh, absolutely. I did my MFA 20 plus years ago now, and in those years of watching publishing evolve, it does seem that the thematic nature of a book has become more prominent. It does make for compelling books in a lot of cases, but sometimes this emphasis seems to take away from the individual poems.

I don’t think project manuscripts are a superior way to go. It doesn't work for most of us, and there actually may be a danger in writing a super thematic collection. Certain parts might be included for logistical purposes, right, rather than standing strongly as poems on their own.

Luke: Yeah, that definitely can be a danger. Another thing that I think has influenced the rise of the project manuscript is that it's so much easier to market. Speaking as a publisher, when a book has a very clear focus, it is so much easier to write book descriptions. It's so much easier to target an audience that might be interested in that topic. So I think publicists and publishers really like project manuscripts. It's hard to sell a book as a bunch of poems that are all really good.

Radha: I am interested in what you were saying earlier about how poems talk to one another, and how they start to develop their own ecosystems of thought. Every poem might not look the same or be talking about the same subject matter. Each poem doesn’t have the same point of view and yet they begin to spark off of one another.

Luke: I think it is temperamental, a neurological thing. I mean, I'm just thinking of when I was in grad school, I studied with Maurice Manning. His latest book is entirely in the voice of Abraham Lincoln. He has always written project manuscripts. I remember asking him about that, how he decides on what project he wants to do, and why he why he writes books that way. He said he can't write any other way. He has to have a project. So you know, poets are just very different. Processes are very different. His process is opposite of mine.

Radha: The common ingredient in many of your poems seems to be empathy. But in order to have empathy, there's humility. Did you think about that consciously—the point of view being humble?

Luke: I thought about the fact that I needed to be more humble, as a person and as a writer. I wanted to explicitly point out my lack in that regard. If the poem is humble, I don't want it to be self-congratulatory about that humility. It's a studied humility, something that I had to work at. It's not something as natural to me as the self-sacrifice was natural for this man who tackled the suicide bomber. I want the poem to enact self-criticism more than I want the reader to think, wow, that perspective is humble, if that makes sense.

Radha: Yes. As a reader, I sense that engagement and struggle.

Luke: It is related to what we were saying at the beginning about the process of discovery. If you're approaching the poem with a predetermined agenda, the poem can become preachy or feel flat.

When I'm teaching poets or talking with other poets, I think it's really important to emphasize the process of discovery, letting the poem develop itself and seeing where it takes you. Robert Frost describes a poem as a piece of ice melting on a hot stove. The ice moves in all sorts of different directions that are organic. You can't predict exactly where it's going to move next.

Radha: I know folks will be curious about the work that you do at Orison as an editor. You put out a prize book and other books every year. What trends are you seeing in the manuscripts you receive at Orison? Is there anything you wish poets knew before submitting?

Luke: Orison has a unique focus on the life of the spirit from all sorts of perspectives. That can be interpreted very broadly. We get manuscripts that are very explicitly about religious or spiritual traditions or experiences, and works that make me think, is this spiritual? What does the word even mean? As the editor of the press, it’s good to ask that question.

I do see a good number of project manuscripts—a book of poems all in the voices of characters from the Bible, for example. Or a book of poems that is retelling stories of the Hindu gods.

What you said earlier is super important for me whenever I'm reading one of those project manuscripts. There are two main questions: Does the collection work as a whole? Even more importantly, does every poem hold its weight and stand on its own, have its own effect? Even though it's connected to all these other poems, and it's in the sequence for a reason, is each poem strong by itself on the page? I would encourage anyone who's writing a project manuscript to be rigorous with yourself and ask that question about each one of the poems.

I see a whole lot of submissions that show promise but that I feel were rushed out to submission. Oftentimes I find myself wishing authors would take more time to revise and refine the manuscript and the individual poems. Poems may be going on too long for their own good, you know, losing their momentum. Or another organization for the poems would amplify the collection a lot better. Sometimes there are simply too many poems in the book, and the weaker ones could be cut.

Radha: Are there any qualities in the manuscripts you see that make you say: Oh, yes, this one's definitely going on to the next round of reading?

Luke: If there's something on every page that makes me want to keep reading. It’s really true. I can't predict what it's going to be but if there's something on every page that engages my interest and my emotions, that impresses me on a craft level, then those are the manuscripts that get bumped up for serious consideration.

There are infinite number of ways to do that. That's one of the really cool things about running a press and being an editor: Seeing the huge variety of work and approaches to writing people take. That's a wonderful thing. I think we need the full spectrum of what poetry can be and what it can do.

—

Learn more about Luke’s work at lukehankins.net.

Upcoming Events / Poet to Poet Community

How to Publish Poetry — Monthly Lunch & Learn

Get clear about what matters to publishing your poetr. The next session is May 1st. Get a free guest pass.

Re: "...it leads me somewhere unexpected, as if the poem has a will and an intention of its own..." I call this "the poem as a ghost in your skull." It absolutely does have its own goals, its own way to reach its blossoming, if only the poet can get out of its way, which takes humility.

Re: "...sometimes this emphasis [on theme in "project books"] seems to take away from the individual poems." I agree. Luke put what's typically missing so well: "something on every page that makes me want to keep reading." That's it: every page. Every poem should be an accomplishment in itself. I guess every poem can't be an absolute stunner, but if every poem could be ... my goodness!

This is so refreshing and interesting! I’ve assumed publishers like project books because the marketing hook is right there. Here’s hoping more publishers will return to/keep looking at collections of strong work. Thank you.