The Poet's Mind is Mycelial

On unlocking "hidden narratives," how grief augments awe, and poetry as life practice—my interview with Cindy Huyser.

As a journalist and researcher (and the poet interviewing other poets here!) I am very used to being the one to ask questions. So it was with delight and anxiety that I answered the following questions posed by Cindy Huyser in anticipation of my reading with poet Sasha West, author recently of How to Abandon Ship, this Sunday at 4pm CT (sign up here to attend online, or if you happen to be in Austin, come down to BookWoman!).

The following interview with Cindy Huyser first appeared here as “A Virtual Interview with Radha Marcum.”

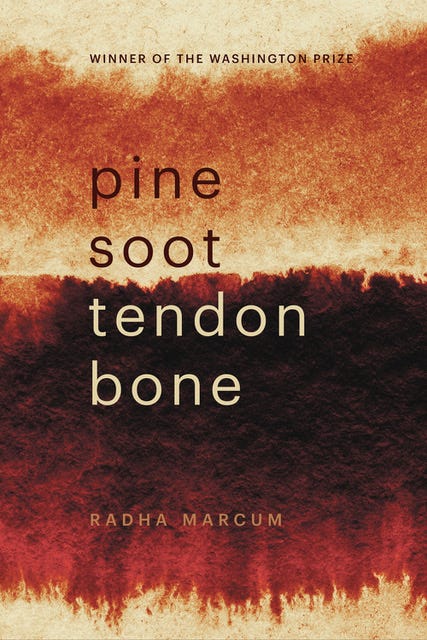

Cindy Huyser: Congratulations on the publication of your second collection of poetry, Pine Soot Tendon Bone (Word Works Books, 2024), winner of the Washington Prize. Please tell us a little about the book.

Radha Marcum: I’m a poet of psyche and science, of language and landscapes that are constantly evolving in response to changes in the environment. The poems in this book came out of disruptive changes in my own environment—wildfires and deaths and other difficulties. Some of the poems touch on personal tragedies that also reflect large-scale, ongoing crises of our era—climate change, mass shootings, the pandemic—but just as many capture otherwise ordinary moments such as watching black-capped chickadees along the local creek or hiking in the mountains near my home in Colorado.

CH: For me, this book’s title is redolent of the bodies of trees and animals and the

transformative work of fire, though I understand its origin to be in the elements of inkstone used in the Japanese painting technique known as Sumi-e. How did you select this title?

RM: When the manuscript was accepted for publication, neither the series editor nor I was completely satisfied with the working title, The Velocity of Sorrow, which is the title of a poem about school shootings. Although the collection contains poems dealing with numerous sorrows, we felt that title was too pointed. I was falling into the same trap as many of my poetry manuscript coaching clients: You want a title that “says it all” yet is memorable. Often this leads to clever abstractions, like my original title, that appeal to the intellect but not the senses. I probably tried two dozen titles that were annoyingly ambiguous before reaching Pine Soot Tendon Bone.

Pine Soot Tendon Bone comes from a line in a poem about a watercolor painted by Japanese American artist Kakunen Tsuruoka while he was interned during WWII. I happened on this painting during the first six months of lockdown during the pandemic. The inkstone Tsuruoka may have used, if traditionally made, contained pine resin, soot, and glue boiled down from animal tendons and bones.

For me, those ingredients are a powerful metaphor for the elements of poetry—which draws on nature and the body, and the transformative changes wrought by circumstances. As landscapes are transformed by fire, our psyches are transformed by suffering. That suffering isn’t only destructive. It becomes the basis for a creative response. The ecosystem revives.

CH: The book’s name comes from a poem called “Hidden Narrative,” a title shared by a

few poems in the collection. Exposing what’s been selected out of narrative (by whoever has the power to control selection) is itself an act of claiming power. Please tell us a little about this thread in the collection.

RM: I’m glad you asked about this. The concept of the “hidden narrative” hinges on a lifelong obsession with what is not said, with stories “hiding” in plain sight. I grew up in the shadow of nuclear secrets, in the American West, where many viewpoints (such as those of Native peoples and marginalized immigrant communities) are deliberately left out of dominant narratives. The first “Hidden Narrative” in the book is the poem about Tsuruoka’s painting.

But for me this drive to uncover “hidden narratives” is about more than filling in missing pieces. It’s about orienting myself to the world with deep curiosity, examining gaps in my own narratives at the macro level (e.g. culture, lineage, landscape) and the micro level (e.g. the molecular composition of trees).

Right this moment, forces beyond our comprehension are revising our bodies, rewriting our trajectories. Cosmic events (supernovae) show up in tree rings, which I write about in the second “Hidden Narrative.” Looking beyond the surface, I am forced to make room for many truths and perspectives. In the space of a poem, I am working against oversimplification, trying to create an experience through language that acknowledges how interconnected and complex and mysterious things are.

For example, my genes are writing me, yet I have so few written records or memories of the voices of women whose genes I carry. Similarly, I “hear” relatively few female literary voices outside of the last two centuries. There are gaps in the narrative where women’s voices should be. The third “Hidden Narratives” (plural) is a braided meditation on my father’s mother, who died when I was seven, and what scraps of Sappho’s poetry we’ve retained. Some of her lyrics survived in shreds of material used to mummify crocodiles intended to accompany someone into the afterlife. Silence has an afterlife, too.

CH: The poems of Pine, Soot, Tendon, Bone witness the indelible marks of both climate change and human-to-human violence, like the March 2021 Table Mesa King Soopers mass shooting in your home city of Boulder, Colorado. How did these concerns come together for you for this collection?

RM: “Swarm,” one of the poems in the book about the Table Mesa King Soopers mass shooting, has an epigraph by Muriel Rukeyser: “Whatever can come to a city can come to this city.” Most of what happens in Pine Soot Tendon Bone happened within a few square miles of my home, including one of the most destructive wildfires in Colorado history.

Believe me, I didn’t go chasing tragedies. They came to me—and all within a few short years. On the other hand, I don’t think of this book as particularly personal. “What can come to a city …” is as true for you—for any reader—today as it was, and still is, for me. Even if your community hasn’t experienced those sorts of events, you probably know friends and family directly affected by climate-related disasters and gun violence. These events, unfortunately, are part of our lives now.

As I wrote and assembled the collection, I worried that absolutely no one would want to read this book. Don’t we already have enough exposure to tragedy?

Over time, I realized that the tragedies weren’t the point—at least not the whole point. Grief’s wide territory isn’t all sorrow. It has a way of sharpening the senses and augmenting awe. Grief made me pay more attention. It put a fine point on the “daily astonishment of being human at all,” as Jorie Graham puts it, heightening my appreciation for the people, trees, plants, animals, rocks—the whole dang universe!—that my life is connected to.

And while I don’t believe in naïve hope or in propagating concepts like resilience (too often oversimplified), I find it fascinating and maybe a bit hopeful that grief and awe can co-arise so poignantly, particularly in the face of “ambiguous losses,” such as those brought about by climate change or a pandemic, in which loss is ongoing. The poems, for me—and I hope for readers—are antidotes to habits of cynicism and complacency fueled by a culture of distraction and dulled empathy.

CH: In poem after poem, I feel the speaker offers an intimacy with the natural world that surprises and teaches me. For instance, the piece called “Poem” opens, “The locoweed that kills horses blooms first / from a crack in one of your constructions. // Also known as astragalus it puts on purple, / rambles its dense leafstalks, throws silhouettes.” How does research figure in your practice as a poet?

RM: As I mentioned earlier, curiosity drives me, and research about a place or a plant or an animal—gleaning from the accumulated knowledge of scientists and other writers—is part of that. Poems don’t typically start in that kind of research, but in direct experience (I guess you’d call that “primary research”).

In the case of “Poem,” I got intensely curious about this tenacious plant that was growing through a small crack in the asphalt of my parents’ driveway. Its blooms were attracting native bees. I thought it was a kind of vetch (genus Astragalus). It was. I found it fascinating and beautiful as a metaphor for the irrepressible nature of living forms, the creative principle around us—and in us. Locoweed can be food or poison, depending on the circumstances. It grows in a high-desert ecosystem that still sustains animals like bobcats yet has been affected by long drought (“the wells’ plummet”). The interior life has its locoweeds and bobcats and depleted wells, too.

CH: These poems offer such a rich sonic palette. Would you tell us a little about how you work with sound in your poems?

RM: Word sounds, for me, are primary in the writing process but remain somewhat inexplicable. Poets’ minds are mycelial. Like fungi breaking down dead forms on the forest floor into nutrients for the next generative cycle, my mind seems to want to break down language to its roots and elemental subparts, including sounds. This breakdown makes language adaptable, malleable, available to form something new.

Like music, a word’s sound can convey feeling before the word is decoded by the thinking brain. There’s research that suggests people sense the same emotions or tonal qualities in particular vowel sounds—for example, “ee” is bright, and “ah” is darker and more somber. Try saying those sounds. Where do they resonate? They vibrate in different parts of the body. They literally feel different.

I learned violin and played in orchestras growing up, so maybe I’m predisposed to hearing language as music, but most poems seem to rise out of my psyche as sound. Even when I’m not paying strict attention, vowel and consonant patterns are woven in from the beginning. I let my ear link words and phrases while images arise associatively. I don’t try to make logical sense in a poem at first. Sometimes this method fails but often the results are beautifully strange.

CH: What surprised you in putting together this collection?

RM: How vastly different the process was from that of my first collection. After I completed the manuscript, I felt relieved, whereas the first time around, I was devastated after the book was done. What was I going to do next? I had absolutely no idea.

After writing the poems that became Pine Soot Tendon Bone over a few years, I shaped the collection within a couple months and sent it off to publishers. Then I promptly moved on to new work. That generative work became a counterbalance to the demands of the editorial process, and it sustains me now through the vulnerability of releasing this book to readers. It takes work to promote a book, and it’s emotional.

CH: In addition to your working life as a prose writer, you maintain an active practice teaching poetry and sharing your knowledge about publishing through your Poet to Poet coaching practice (https://www.poettopoet.com). How does your literary citizenship work feed your poetry? How do you make room for your own writing?

RM: A book of poems arises from an ecosystem that is as much external as it is internal. No work is solitary, yet outside of MFA programs, conferences, and community writing programs, poets mostly have to build their own ecosystems to sustain the practice of poetry long enough, with enough diligence, to create a body of work. What’s more, poets aren’t often encouraged to think of their work in those terms—developing a body of work—and there are scarce resources to help create a book, never mind trying to find a publisher. That’s almost entirely up to each individual poet.

I want to shift that. A couple years ago, I started interviewing poets about their new books and the processes behind them. I publish those conversations on Substack and YouTube (poettopoet.substack.com). I ask questions like: Where did the book start? How did it develop? What approach helped in structuring the collection? What was their strategy for finding a publisher? And so on. Each poet, and each book, has a different process. That is fascinating—and instructive. But there is a common theme: Almost everyone says they couldn’t have done it without peers, mentors, etc., who helped fuel and focus their work.

My students and coaching clients wanted a space to talk about the process, so I started offering Zoom groups and occasional classes (see poettopoet.com). In those, I’m very open about the work behind my two books. I’m not interested in conjuring a veil of poetic mystique. After all, I wouldn’t be answering your questions about this second book if I hadn’t been sustained through this difficult work by my own writing community.

Writing poetry is a life practice. The timeline for publishing a poetry book is long, often longer than for other genres. Being in community with other poets and teaching sustains my work, and I hope that I can help sustain the practice for others. I want to nurture ecosystems where poets can thrive.

Upcoming Events & Classes

It’s not too late to join me for …

How to Publish Poetry — Lunch & Learn (Virtual)

Are you working on a full-length poetry manuscript or chapbook, or building a portfolio of journal publications? Learn how to work smarter and overcome common obstacles to getting published during these monthly sessions in 2024. Jump in any time. Our next session is September 11th. Get a free guest pass.

Pine Soot Tendon Bone

"Radha Marcum writes unflinchingly and with a rare synthesis of lyric and scientific intelligence, investigating just what it is to exist with consciousness now.” —Carol Moldaw, author of Beauty Refracted

"Writing poetry is a life practice." I love this line, Radha. It suggests that this writing life practice is the ultimate motivation, the ultimate sustainable satisfaction. And yes, building an ecosystem of other poets, other thinkers, others who value what we do as poets is essential yet a constant challenge whether we are post-MFA or non-MFA writers like I am.

Your Poet-to-Poet community on Zoom helps--it is wonderful to hear writers from around the world gather around the poetry-fire. Your new book is lovely, and I look forward to your reading in Austin this weekend!