A few days ago, I received this note from a workshop participant:

I’m feeling insecure about my poems and unsure of what to do. The workshop doesn’t seem engaged with my work. Is it because of _______ [insert an aspect of the poems]? Maybe I should stop writing and focus on submitting, hoping publication will give me validation?

My heart ached for this poet. I could relate all too well, having been in that conundrum many times.

As a workshop leader, I do everything I can to help poets gain insights that fuel their creative process, rather than shut it down. But workshops are never perfect. Many factors—both internal and external—are beyond our control.

The real question isn’t whether feedback (or a lack of it) will send you into a downward spiral, but rather, what to do when it does.

What Matters Among the Many Factors?

You’ve probably heard advice like “ignore irrelevant feedback” or “develop a thicker skin,” but have either of these strategies ever helped you return to your work with clarity?

Yes, we need to be resilient. If you're only seeking praise, writing might not be for you. Constructive feedback is essential to growth. But it's important to consider what kind of feedback actually helps you see your limitations while still encouraging you to keep writing.

I helped that participant reframe the workshop experience along these lines:

1. Know Your "Zone"

Your "zone" is the intersection of your thematic and stylistic preferences. Most of us don’t write poems from a purely conceptual standpoint, so this often becomes clearer later in the writing process, as we've been discussing in the How to Publish Poetry Lunch & Learns this year.

If you want to empower yourself in workshops, start by investigating what drives your work. What obsessions and stylistic choices define your unique voice—your “zone of genius”? If that sounds overwhelming, simply list what matters to you in a poem. Is it emotional or tonal impact? Narrative flow? Logic or illogic? Smooth or disruptive line breaks? Traditional forms or unconventional juxtapositions? Lyric qualities?

Knowing and naming your zone helps you filter useful feedback from comments that don’t align with your vision.

2. Recognize Others’ Preferences as Just That—Preferences

It should go without saying, but poets bring their own preferences—their own “zones”—to workshops. Not all poets can step outside their comfort zones to fully appreciate other styles. The best workshop leaders and participants try to understand your unique approach to writing. When they don’t, see it for what it is: a natural limitation, not a reflection of your work’s value.

3. Silence or Enthusiasm Aren’t Always Telling

Silence doesn’t necessarily mean disengagement. Often, poets in workshops have less to say about works that seem well-formed or nearly finished. If you write more lyrically than narratively, or your poems are surreal, elliptical, concise, or nuanced, you may encounter more moments of silence.

On the flip side, I’ve seen overwhelming enthusiasm for poems that still had a lot of room for improvement. It’s easier to talk about a poem with a million entry points, even if they don’t all connect.

Build Relationships with Trusted Readers

Finding peers and mentors who truly "get" your work is invaluable. Not all poets—even experienced or famous ones—will understand your style. It’s crucial to seek out trusted readers who resonate with your voice. When you find them, nurture those relationships.

I know poets who stopped seeking feedback altogether, and many of them eventually stopped writing. How sad is that?

We’ll all face moments of doubt. What brings you back to the page with a creative mindset? Share in the comments.

Upcoming Events & Classes

Poets House: Anatomy of a Standout Manuscript (Virtual)

What are publishers looking for? It varies, of course. But certain qualities do separate standout manuscripts from average ones submitted to most publishers. This class will cover the seven essential qualities of standout manuscripts, and frame your next steps in creating a strong and delightful book of poems. 3 hours on Saturday, October 19, 12-3pm ET (10am-1pm MT), $105. Register.

It’s not too late to join me for …

How to Publish Poetry — Lunch & Learn (Virtual)

Are you working on a full-length poetry manuscript or chapbook, or building a portfolio of journal publications? Learn how to work smarter and overcome common obstacles to getting published during these monthly sessions in 2024. Jump in any time. Our next session is October 2nd. Get a free guest pass.

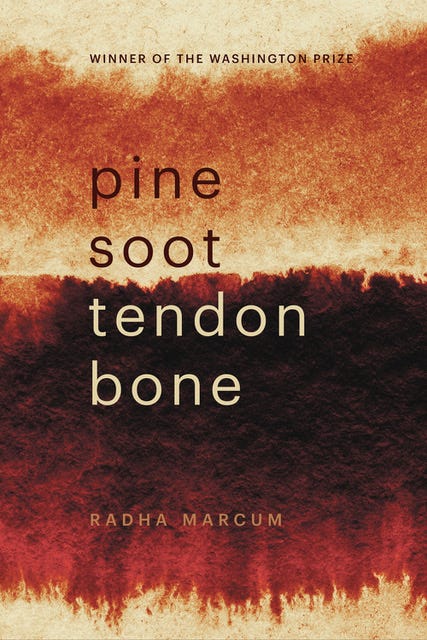

Pine Soot Tendon Bone

"Radha Marcum writes unflinchingly and with a rare synthesis of lyric and scientific intelligence, investigating just what it is to exist with consciousness now.” —Carol Moldaw, author of Beauty Refracted

Thanks for this essay, Radha. I too struggle to stay motivated in workshops where I'm not getting useful feedback. You are reminding us that "useful feedback" comes from sources who have inherent limitations and preferences, not always aligned or compatible with our own. It's easy to feel discouraged in that case. I think this parallels submitting to noncompatible publications/editors/judges.

Maybe identifying certain "zones" (i.e., tone, theme, style, etc) in others' poetry could help identify which poets are more likely to understand how and what I write. Something to think about...

I think one trick to get a class talking is to ask, what do you notice? I had a workshop facilitator who only ever asked us to call out objective comments, at the most basic level if nothing else—I notice no punctuation, short lines—which inevitably led into more subjective comments. There aren’t many “how to give feedback” classes offered; and I think especially beginning poets don’t want to spend money to learn how to read poetry instead of learning how to write/ improve their own, not realizing that learning to give effective feedback is an amazing way to grow your own work. Facilitators need to recognize that many of us don’t have MFA’s, haven’t had formal training in reading a poem or giving feedback, and providing resources on how to do that, even if it doesn’t taste up class time, can be invaluable for the poets they are teaching. It’s also hard, early on, to have the confidence to say what we think, we are afraid of sounding stupid if we don’t get something—especially in work that is atypical, appears personal/ trauma based; we aren’t taught to look at the craft of the poem so focus on the content. If a writer is saying, I don’t think I did the prompt right, they certainly don’t understand their perceptions of a poem they read can’t really be right or wrong.