Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash

This week, the Poet to Poet community gathered on Zoom to discuss poetry manuscript titles. They’re notoriously challenging (unless you’re Rebecca Aronson who says her latest title was “easy”—kudos, Rebecca!). More than in any other genre, approaches to poetry-book titling varies so widely there is almost no approach you couldn’t take.

It helps to think of the reader. What does a good title do for a reader who is completely new to your work?

Generally, we agreed that a good title orients us without narrowing our viewpoint. It alerts us to the primary impulses of the book. It may suggest an activity or a mode, how to orient oneself in the book’s territory.

Good titles are signs, not summations.

A good title opens a door, suggests multiple meanings.

It has ambiguity and mystery—but not too much.

It may be abstracted from more literal subjects in the manuscript.

It might name an object representative of the whole.

I did a little exercise with the books on my nightstand and came up with these loose categories.

A phenomena, a force:

Sight Lines, Arthur Sze

Anchor, Rebecca Aronson (“anchor" is both noun and verb! Brilliant)

Twice Alive, Forrest Gander

Radial Symmetry, Katherine Larson

Thing as metaphor:

Pilgrim Bell, Kaveh Akbar

Map, Wisława Szymborską

Borrowed from culture, other disciplines:

Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, Diane Seuss

The Dream of Reason, Jenny George

The Gospel According to Wild Indigo, Cyrus Cassells

Instructive:

Be With, Forrest Gander

Heart First into This Ruin, Wanda Coleman

The Trees Witness Everything, Victoria Chang

Situating in place/time:

In the Lateness of the World, Carolyn Forché

So Late, So Soon, Carol Moldaw

Interglacial, James Richardson

Moving to Climate Change Hours, Ross Belot

Notice how these titles each have a distinct tone created by brevity or length, by repeated word sounds like the “i” in Twice Alive or Sight Lines and rhythms like the triplet beats in In the Lateness of the World or iambs in The Dream of Reason or the emphatic Be With.

Working titles vs. final titles

We discussed how a working title is important to drive your work forward, to hold open a space of inquiry. But it often isn’t the optimal final title.

The working title of Bloodline was Oppenheimer’s Dog. It still had that title when the manuscript was selected for publication by 3: A Taos Press. “Oppenheimer’s Dog” is a poem in the book that comes from a story passed down to me from my mom about J. Robert Oppenheimer’s literal dog. My grandparents lived near the Oppenheimers in Los Alamos’s early days. That story about my grandparents hearing that dog’s incessant barking was a sort of inciting incident for the book. The literal dog became a metaphoric one representing the scientists’ better instincts and their later regrets. The sound of that dog barking becomes, in the book, the sound of regret and how that regret reverberates through generations.

For me, it was the perfect working title. But it didn’t describe the whole territory of the manuscript, which includes landscapes and stories outside of atomic weapons development. The book isn’t about Oppenheimer, it’s about my family, about inheritance, about blood connections and connections to blood spilled by war, and about our tenuous connections to place (like the ephemeral rivers, the lifeblood of the West).

Very late in the process of editing the book for publication, Bloodline as a title occurred to me while I was hiking an arroyo in a desert canyon. Typical, right? As long as I was looking for it directly, the title eluded me. It arrived when I forgot about the mess and became more receptive.

Also, the title was in the language of the book already. I think this is often the case—your ideal title is already somewhere in the mix, it just needs to rise to the surface.

Freedom to explore

Personally, I’m drawn to a title that grounds me in the book’s territory without being too pointed, too directive. A good title says hey here’s this territory to explore (opening up the experience) vs. telling me exactly what to see (reducing the experience).

I’m curious: What do you look for in a book title? What’s your manuscript’s working title? If you’ve published a book, how did you arrive at the title?

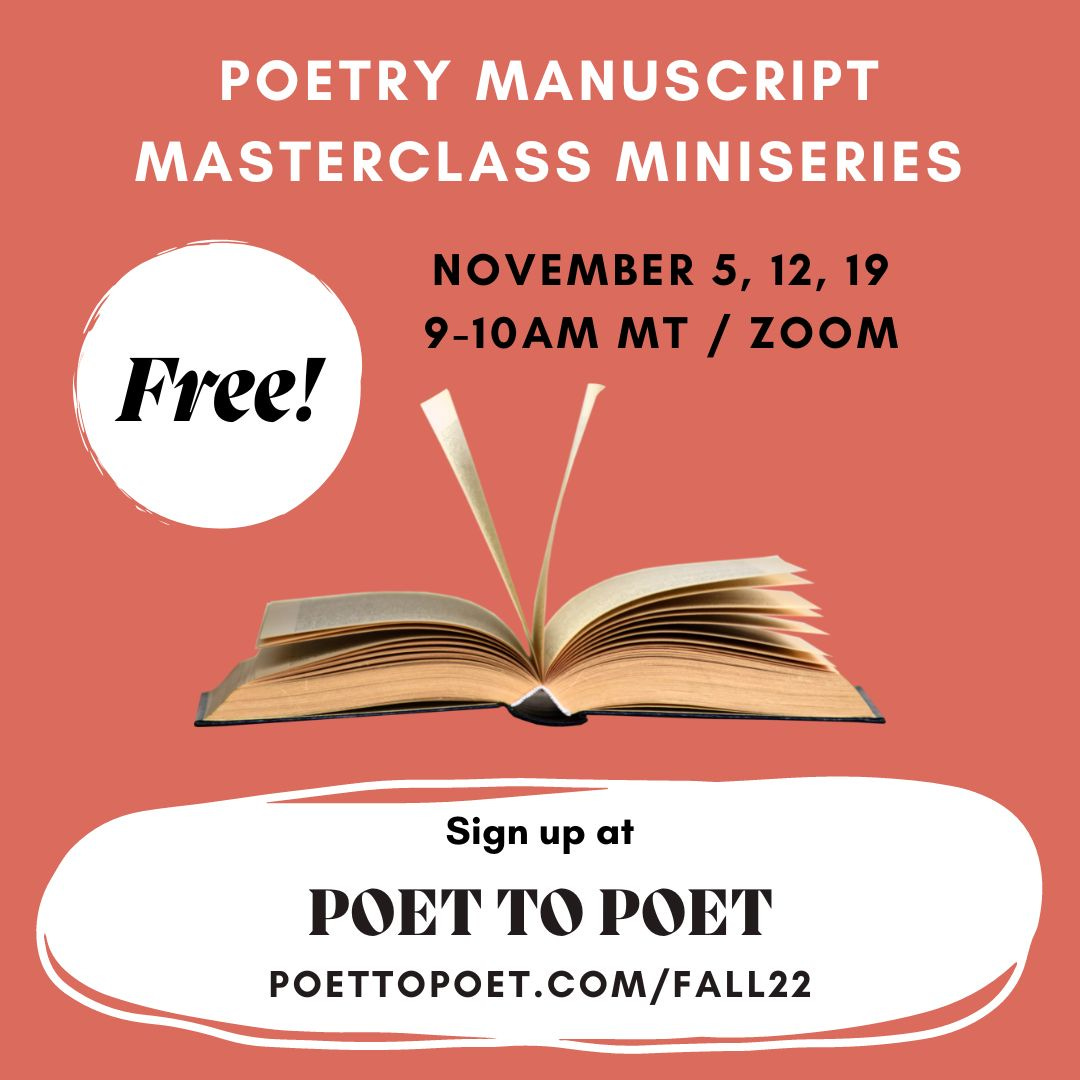

Do you have a stack of poems just waiting to be organized into a beautiful book? Or a manuscript that’s halfway there but needs … something? Learn the essential steps to creating a standout poetry manuscript in this free masterclass miniseries. Know where to start, what to do next, and when to start submitting.

This poetry manuscript masterclass mini series is for poets in any stage of creating a manuscript. Join for one class or for all three.

November 5: Anatomy of a Standout Poetry Manuscript

November 12: How to Sequence Poems

November 19: Common Mistakes—and How to Avoid Them

All classes take place on Zoom from 9-10am MT (8-9 PT, 10-11 CT, 11-12 ET)

I wonder if another good (and simple) approach to naming a book of poems is just to use the title of one of its poems. This is such a common practice in poetry books, music albums and short story collections.

For example, Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars also contains a poem with that title. Is it the book’s best poem? I wouldn’t say that, but it does hint at the book’s themes: space and the questions that contemplating space brings to mind.

Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited also includes that song, but is it the most memorable song on the album? Uh, probably not; the album also includes Like a Rolling Stone. Yet the album title, with the word Revisited, is intriguing.

Some of this might just be a numbers game. You’ve already gone through the title-naming process for dozens of poems. Surely one of the titles is really, really good.

Examples: Work, for the Night Is Coming (Jared Carter); The Gods of Winter (Dana Gioia); For the Union Dead (Robert Lowell).

One could argue that Aronson’s book could have been called Dear Gravity. Perhaps Anchor has greater meaning once the book has been read, but as an advertisement, an enticement, it feels slightly abstract to me.

It reminds me a little of Gregory Pardlo’s Digest. Pulitzer or no, I can never remember the title of that book and it contains no poem with that title.

One advantage to using a poem’s title as the book’s title is that if you remember one, you remember the other. Another advantage might be less risk of an eye-rolling construction with an air of strained profundity that tries to encompass too much.

My book's title, High Stakes & Expectations, is in two definitive parts, and the title was inspired by comments noted on the manuscript by one of my teachers who counseled me on the work. She kept noting the danger, high stakes, and not what I expected, and variations of those words, throughout the book. The book's first chapter is all about risks (real and imagined) and the second is about hope which an acquaintance of mine defined as "expecting something new," which became another inspiration for the second half of the title.